|

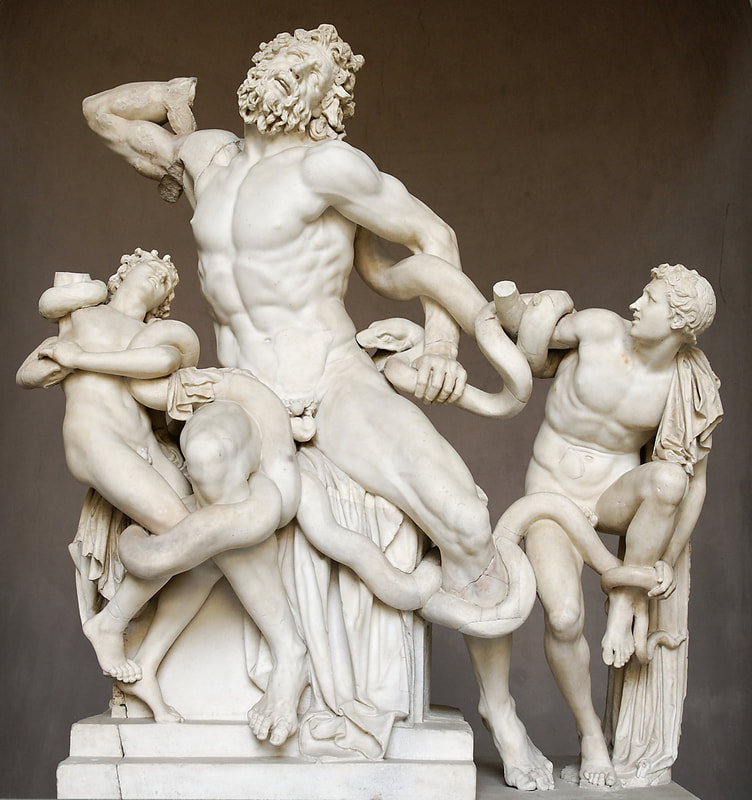

The New Laocoön I don’t know whose bright idea it was to call it that. The original sculpture of Laocoön, the Trojan priest, and his two sons was recovered from the Baths of Trajan in 1506 and is now in the Vatican. It is one of those great works of art that is copied, re-copied and re-interpreted. However, the one I worked was not carved in marble, but made of plastinated, human tissue. Two sons, or at least two beautiful young men – no father – no priest. "Tony?" "Speaking." "Thought you were a man." "Toni with an eye: short for Antonia." "Steve told me to call you. Can you leave now?" "What's the problem?" I asked. "Steve said you did their feet." He could only mean the New Laocoön. “It’s in Geneva. At the Freeport.” It was not a professional job. The thieves had ram-charged the storage facility. The dumper truck was still lodged inside the remains of its fortified door. The gendarme on guard, stamped out his cigarette, looked at my legs and then waved us through. They had only looted the one security cage. I had no idea why. Art thieves are not the clever people you see in movies. Most contemporary works of art have impeccable provenance and are difficult to sell illegally. They are mobile assets, but not liquid. As for stealing on commission: serious crooks stick to paintings not biological works of art. The godfather would rather have a Renoir than a pickled shark any day. "Steve said you could help." The man who thought I was a man looked awful. He was facing a big insurance write-off. I got into biological fine art by accident. Post-doc, I made human, anatomical specimens for medical demonstration. The technique uses polymer to replace the fluid of natural tissue: the specimens do not decay. They turn into solid demonstration models. Anything from a tumor to a whole body can be turned into a sculptural object. A few artists took over the idea. The problem with pickling things in formaldehyde is that over time they lose color and definition. The pickling solution goes cloudy, too, and it can cause cancer. The New Laocoön (TNL) when first shown, was an immediate succès de scandale. Is it possible in the art world to succeed any other way these days? The naked, male bodies, suspended inside a vitrine, were locked in an amorous embrace. Two beautiful young men: two plastinated, human bodies with a graphite-like patina that turned them into classical sculpture. They had been real men, but who were they? Were they really lovers? How did they die? People kept asking the same questions. People kept coming to view the work, too. At one point, Interpol got involved: wanted to know if the bodies were legally sourced. But the Croatian artist wouldn't say. The French issued an arrest warrant. The artist went to ground, and TNL went to MoMA. Plastination is not a simple process. Let's say you want to make a medical model of a flayed human arm to show the muscles. After the skin is removed the arm is dehydrated, defatted, impregnated with polymer, and then cured. It takes a lot of time and care. In the case of the lovers the fresh bodies would have been molded into that famous embrace before being immersed in acetone. A couple of years ago I had repaired a small chip on the foot of one of two figures. I guess that is why Steve thought I was the person to call. "What do you think?" asked the insurance man. The thieves had broken open the packing case, smashed the vitrine with a hammer, severed the suspension wires, manhandled the two bodies to the ground, levered them apart and stolen one while leaving the other. Its right arm was snapped away at the head of the humerus. "Can it be restored?" What was the point, I thought, without the other figure? If I couldn't see the point Steve could. He was hopeful, I suppose, of tracking down the missing body and reuniting them both. He was not short of funds. The loss assurers were not too keen on writing it off either. A few million on restoration was better than forking out thirty to forty million in compensation. We rented a secure space within the Freeport, and I began fitting it out as a studio to handle the potential restoration. Meanwhile, I removed a flake of that wonderful patina material, and sent it to a friend in the Mauritshuis studio. We tried to contact the artist but got no response. Then a couple of days later we discovered through his London dealer that he had been murdered in Prague. A quarrelsome character, apparently: a bit like Caravaggio, I suppose. I went back to my own place in London for a few days. I had to complete a small job on a taxidermy exhibit by Tidemann. A couple of days after my return I had dinner with friends, then walked back alone over Battersea Bridge Road and down Prince of Wales Drive. It was late. It began to rain. I know that part of London well. I have had a studio there for years: a long time before speculators jacked the prices up. For some reason it suddenly felt unfamiliar. There was nobody about aside from a tall man on the opposite side of the road. I assumed it was a man. He seemed to glide along the shiny wet pavement keeping pace with my steps. When I got back, I gave myself a stiff drink and turned on the Mac to check the mail. There was a quick message from the Mauritshuis. They were still working on the patina recipe but had identified one of its ingredients as smalt. That was a bit of a surprise. Smalt is powdered glass colored with cobalt. They were already familiar with it, she wrote, because Rembrandt used it. It was I knew popular with painters in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It adds a luminous zest to the painted surface, although it does not age too well. Although it was late, I decided to watch a movie on YouTube. I first watched ‘Der Golem’ at the old Electric Cinema in Notting Hill. It is a salubrious place now, but then it was home to stray cats and the lighting was very atmospheric. It all added to the mood of a silent, German, horror movie made in 1915. Watching it on YouTube was quite different. Set in the Jewish ghetto of sixteenth century Prague, the plot is complicated, but the golem is a clay monster animated by a written spell set in an amulet impressed into its breast. Anyway, I watched that for a bit, felt sleepy, finished my drink, turned out the lights and took a quick look through the window to see if it was still raining. It was, and I caught a glimpse of the same tall man. At least I think I did – best not to watch horror movies before going to bed. The next morning, I got a call from the insurance man. He had already been over to Prague. "Sounds nice," I said. "Not really." "No?" "Went to see his studio. You know. See if there's anything we can use." "Useful?" “There's lots of stuff including notebooks. Can you come over and see it?" “Not right now. I've got too much on.” "I'll send it to you in Geneva." "Is that OK with his agent?" I asked. But the phone went dead. Back in Geneva I set to work in earnest. The arm fracture at the head of the humerus revealed raw-looking splinters of plastinated bone, muscle, and skin. Somehow, I had to fit it back together again. The best plan, I thought, might be to grind down the splintered fractions to create a clean join. I could use a rigid, titanium pin. If that worked, I might use mortician's wax or wound filler. The insurance man had already sent me a good set of provenance photographs. If I had to free sculpt the arm, I did not want to get the position wrong. If ever we did recover the second lover, the refitted arm had to be a snug join around the upper back and shoulder of its companion. It made me think of the Discobolus in the British Museum. It is a Roman copy of a Greek bronze. The head was broken off and replaced by a restorer the wrong way around. Instead of looking at his discus the athletic thrower has a brilliant view of his own knees. Restoration is always a mixture of art and science. I would have to think very carefully about the arm. In the meantime, I could check the rest of the figure. The best idea, the logical way of doing it, I thought, was to set myself a daily schedule of looking at things detail by detail. After making the schedule, I decided to turn in for the night. Our temporary studio was a tent-like structure of transparent polythene sheeting in the middle of the small hangar we had rented. The hangar itself was air-conditioned and a filter kept the tent dust free. The body rested on a foam mattress on a dissection table and was covered with a clean cotton sheet. I had a surgical lighting system set up. It was a neat arrangement. Seen from outside, the tent looked like a huge, glowing cube of ice. The electrics came via a switch box at a side entrance to the hangar. I tidied up the photographs on the righthand side of the dissecting table next to the intact, left arm, and tugged the sheet over the body. I left the ice cube, hit the switch by the door, unlocked the door, let myself out and then re-locked it. The following day I had a late start. I took breakfast in my hotel and read the papers rather than my laptop. I saw that another work by The New Laocoön artist had done well at Christie's, New York. A record price, it said. Not much use to its late creator, I thought, but then artists who do so-so in life sometimes do well in death. I kept puzzling over the right arm repair. There was no way I could do it without the other body unless the owner decided to restore it as a single piece. I took a taxi from the hotel out to the airport. On arrival I went through the rigmarole of checking in, unlocked the hangar, hit the power switch, and prepared to start on my checklist. When I stepped into the ice cube, I had a feeling that something was amiss. I looked around. Everything seemed OK. I sometimes get strange feelings when working alone. However, I turned on the Mac, printed off my checklist, put on my surgical gloves and went to remove the covering sheet. The tip of one of the fingers of the left arm peeped out from under the sheet. It rested on the stack of provenance photographs, and the top photograph showed the face of the missing figure. I was stunned. I was sure I'd covered it up. Perhaps the photograph had slithered off the pile and under its finger. My phone rang. "You, OK?" "Fine, " I said. "We got quite a lot of stuff from Prague. Production notes and so on." "Right." "On its way." "Right." "I'll be over next week. Got a meeting with Steve." "Any luck with the other figure?” I asked. But he'd already gone. So, the agent didn't mind our borrowing his dead client's notebooks, but then he probably had an eye on their eventual auction. If they turned out to be useful in a forensics case, it would make them more attractive at auction. However, while going over the body, I found something not included in the provenance notes. There was a significant wound over the abdominal aorta. Since the artist had applied the patina after the figures were fixed, those parts of the chest and abdomen not visible in the finished work were in their usual, raw, plastinated condition. Furthermore, the artist or someone else had made a tissue repair before plastination. When I probed the wound a plug came loose. It filled what looked like a puncture wound and had an odd composition. Although plastinated, like everything else, it was a tightly rolled piece of something: perhaps animal parchment. It occurred to me that it might even be human parchment. Anyway, I took a photograph and emailed a JPG to someone I knew in forensics. When you work in my line, most people you know are in the death and resurrection business. I placed the plug in a kidney dish on my instruments trolley. And aside from the wound and humerus fracture, the rest of the cadaver looked fairly all right. A couple of days later a small crate of stuff arrived from Prague. I set up two wooden trestle tables outside the ice cube and started to arrange the contents. There were over a hundred drawings and scribbles, but none dealing directly with TNL. I was lucky with the notebooks because one dealt with prepping the bodies. Both men died, the notebook suggested, from ballistic trauma. That was puzzling because there was no evidence of that on the body I was looking at. The background story seemed to be that the two men died trying to save one another. They were lovers who had found themselves on opposite sides in some ethnic conflict – so the artist said. When I spoke to the insurance man again, he suggested the Bosnian War. "Why Bosnia?" "Dates, really. It was in circulation by ‘97, wasn't it? And then it was in that French show in 2000. The Bosnian war was ninety-two to ninety-five, wasn't it?" There was talk of a major retrospective. Wouldn't it be great, Steve's agent said, if TNL was ready for that? I dare say it would, but the other body was still missing, and I had done as much as I could in the meantime. I went back to London for Christmas and was going to take a short holiday afterwards when I got a call early in January. "You'd better get back here. We've found it." It was big news. You may recall it. The thieves were not international villains. They were family relatives of the dead man. Scandalized by his use in a profane work of art as they saw it, they decided to recover his body and give it a proper burial. The other body was of no interest to them. It was true that the two men had been lovers. That had outraged the family, too. The lovers were of different religions, came from different ethnic groups, and were gay. They made a great work of art and caused a great deal of personal distress. As a piece of sculpture, they were, as I said, a succès de scandale but one of the men, at least, was a disappointment and source of abiding grief to his family. Exhuming the body from its new grave and returning it to Geneva was a diplomatic and logistical nightmare, and fortunately I had no part in it. The insurance man was not really forthcoming on the matter, and I suspect it cost him plenty. As I said, he was facing a bill of forty million, so a million here or there was not that important. Given the storyline, once TNL was properly restored and passed through a couple of blockbuster shows, it might well double in value. Scandal, murder, and theft always jack up the prices. The agent chartered a jet, and the body came back in style. A pack of news hounds recorded the off-loading of the coffin. Steve came over from New York for five minutes and gave an interview about its artistic importance. It was a worldwide icon of the gay community and so on. I kept out of the way. Full restoration of the piece was not a foregone conclusion. I did not want to answer any awkward questions, but the agent arranged a photo-op for a chosen, few inside the hangar. I tried to keep my comments short, and after we opened the coffin for photos we locked the place down again. Steve dropped in, shook my hand, told me he was relying on me, and shot off to New York again. In the eerie silence following all the fuss, the agent and I sat on a couple of chairs by the coffin. It was propped on stout, steel trestles. A second table had already been delivered to take the recovered body, and I placed it to the right of the first. When I eventually joined them together again, I would need to bolt the tables together. But that was a long way off. Restoring each of them separately would take a while. "What do you think?", he asked. "We'll see," I said. "Steve is relying on you. We're thinking of a special exhibition next year." "Are you?" "You, OK?" "Fine. Give me a hand, will you?" "What?" "I need to shift him to that table. Use a pair of these gloves." "Me?" "Can't see anyone else, can you?" Even after a couple of weeks, the spooked feeling did not go away. The body had been washed and shrouded preparatory to its burial, and the washing had removed much of the patina. I would need to make good the plastinated tissues, rejoin the bodies and re-polish them. It was going to be a long job. While inspecting the second body I was also considering the possibility of taking on an assistant. On the plus side, the second body was not too damaged except in the abdominal area where the thieves, where the family, had levered apart the two bodies. The plug of whatever it was, I now saw, fitted inside their conjoined bodies. With my back to the first body, while inspecting the second, I eased back my wheeled chair to get a better view of the abdomen. The two bodies on their separate tables lay side by side with me in between. As I moved back and tried to better angle the inspection lamp, I bumped the table behind me. It was a fairly gentle tap but sufficient to dislodge the body and roll it sideways. Since there was no right arm to stop it, the next thing I knew was that its intact left arm was reaching across my shoulder towards the second body. I shot out of my chair, a stupid reaction, and the reaching body would have fallen had its hand not come to rest on the arm of the second body. I took a couple of days off after that and ignored the phone. The agent was now in the habit of calling every day. "How was it going?" "When would I finish?" Steve had been talking to Larry and they were keen to get the TNL back on show. I did finally answer one of his calls. "I need an assistant," I told him. "You, tell me. Anything you like." "I'm not sure who." "Whoever." The truth was I needed live human company. It was my contact at the Mauritshuis who suggested Lucy. She had just finished an art conservation degree. She was very good, my contact said. Could certainly help with the re-patination. Would jump at the chance to work with me. Would jump through fire to work on The New Laocoön. Well, she did not have to jump through fire she just had to join me in Le Freeport in a hurry. Six months later we were ready to reunite the lovers. Steve was pleased, Larry was pleased, the agent was crunching numbers in New York, and Lucy, standing in one corner of the ice cube, was holding the detached arm. We had an approximate angle for its fixation, and she had come up with the brilliant idea of using a flexible, spring-like connection rod. After rejoining the bodies, we could manipulate and lock the encircling arm in place with adhesive and use filler to free sculpt the deltoid fracture. The Mauritshuis had also come up with something approximating a workable patina recipe. Temporarily, the two bodies lay side by side under an electric hoist with their two tables bolted together. Lucy placed the arm with its flexible pin next to its owner. Final fixation and rebuilding could be done after we reunited the lovers. We stood back, admired our handiwork, and decided to call it a day. A little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands, and I was wide-awake again. The job was still complicated, and I was going over potential problems. I got up at five, took a shower and then set off by taxi. I left a message with the night clerk for Lucy. Said I would see her whenever she was ready to join me during the morning. Dawn was breaking when I arrived. I went through the usual rigmarole of checking in and then unlocked the door. As I reached for the light box inside, I heard a noise. It was a voice. No, voices. Not talking. My first thought was that someone had sneaked in, but how? There it was again. I flipped the switch. There was movement inside the ice cube. The two bodies, in an embrace, were moving to and fro. I stepped back and hammered on the door to get out. I then realized that all I had to do was open it. I returned to the hotel and was hurrying across the entrance lobby when I met Lucy. "You're up early," she said. I nodded. "You, OK?" The day clerk came across and gave her my note. She took a quick look. "You left early." "Just got back," I said. "Problem?" "Felt a bit spooky on my own," I said. So, I came back. Shall we go?" "Soon as I've had breakfast," Lucy replied. Back in my room I took another shower, ordered coffee from room service, tipped in a miniature of whisky from the icebox and sat down to check my email. The coffee plus the whisky calmed me down. What an idiot I was. "Thanks for photos – difficult to say without seeing artifact – like you said looks like roll of parchment – tried magnifying the writing – see file. Best K." I had not noticed any writing on the roll of parchment, but if so, plastination would not necessarily erase the ink pigment. I must look at the thing again when we got back. It was still in the steel kidney dish on my instrument trolley. I gave Lucy the key. She entered first, pushed back the polythene sheeting and entered the ice cube. "Thought you said you were here just a few minutes," she said. I joined her. The two bodies, all arms, were reunited in their famous embrace. "Looks good," she said. Then I remembered the scroll thing and looked at the instrument tray. It was gone. My phone rang. I asked Lucy to take it while I took a closer look. "Hum. Yes. She's here." I waved my hands to say I was busy. "Bit busy. Yeah. We got them back together again. Toni did it this morning." She rang off. "Mr. Insurance man." "Who else?" "Take a close look at his arm." I said. "Sure." She examined the fixed arm more closely. "You got it just right," she said. "A really lovely job." Wilf Tilley Wilf Tilley is a neurophysiologist, artist and writer living and working in Tokyo. Read another story by Wilf Tilley at The Ekphrastic Review.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|