|

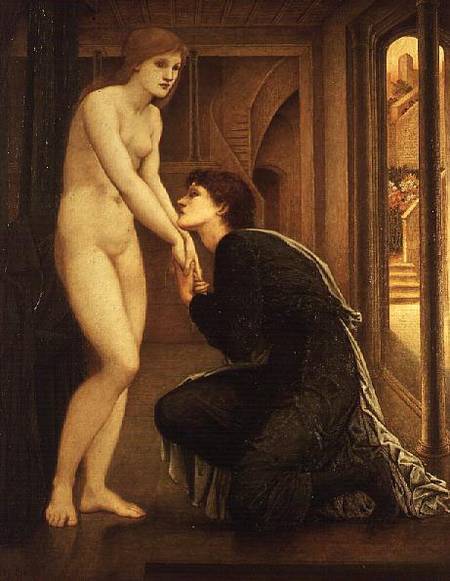

The Painter’s Wife The painter conjured her down from the painting, and fell on the floor, exhausted. He slept without dreams because the time for dreams, vivid as they were, was finally over. When he awoke, she stood motionlessly over his supine body, and her gown smelled of fresh paint. Her face was frozen, her muscles rigid, her eyes glassy. The painter turned his head and saw her likeness still on the painting. There, she was smiling, a faint but warm smile. He turned again, and there she was, alive, but as unwelcoming as an icy rain. She couldn’t be in both places at once; though no scientist, he knew that much. He parted his lips, about to ask her to move, to stand by the painting, so he could see and decide for himself, but she lowered herself to him. She was smooth under her dress, and warming up quickly to his touch. Now, a day later, she smiles as if she’s used to moving her lips and squinting her eyes. Her curly red hair falls, full and thick, on her pale shoulders and back, in long strands that have lost their canvas flatness and brush strokes. Her smile is an enigma with the frosting of promise. Her breasts and belly carry his fingerprints. They exchanged rings once and DNA on several occasions. “I love you to death, if you’ll forgive me such a cliché,” she says, testing the sharpness of her nails against the skin of her hand while watching her husband shaving. She seems fascinated with sharp objects—a curious trait for someone who spent all her life inside the vulnerability of woven cloth. The painter tried to get her next to the painting, to see them together, but failed. They never exist in the same frame. At least he can’t see them, which is the same to him. He blames himself: his studio is too big, she’s too quick on her feet, and his vision is not as good as it once was. Nodding to her words, the painter cuts himself with the razor. He winces, but the little pain doesn’t prevent him from granting her poetic license to speak any way she wants. She steps closer to the painting, walking softly like a cat. The painter blinks. One of them will be gone now. Maybe, all three of them, even the painting, will be gone. He’s not certain of anything anymore. Her hair and fingernails shine like a burning sun, and he brings his hands up to protect his face. Mark Budman This story was first published in Fiction Southeast. Mark Budman was born in the former Soviet Union, and he speaks English with an accent. His writing appeared in Five Points, PEN, American Scholar, Huffington Post, World Literature Today, Daily Science Fiction, Mississippi Review, Virginia Quarterly, The London Magazine (UK), McSweeney's, Sonora Review, Another Chicago, Sou'wester, Southeast Review, Mid-American Review, Painted Bride Quarterly, Short Fiction (UK), and elsewhere. He is the publisher of the flash fiction magazine Vestal Review. His novel My Life at First Try was published by Counterpoint Press. He co-edited flash fiction anthologies from Ooligan Press and Persea Books/Norton. http://markbudman.com

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|