|

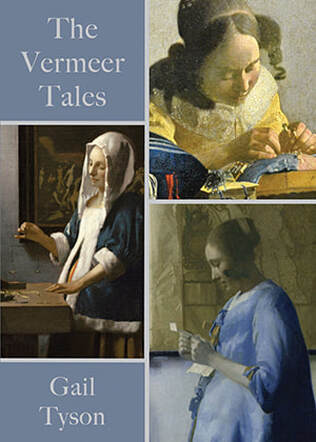

The Vermeer Tales by Gail Tyson (Brunswick, ME: Spring Leaves Chapbook Series/ Shanti Arts Publishing, 2020) The Vermeer Tales: Linda Parsons Reviews and Interviews Gail Tyson We may not be aware of it, but we are always seeking balance—emotionally, physically—in tune with our inner clocks, the broader ticking of time and seasons, day to night, joy to grief. In The Vermeer Tales, Gail Tyson offers a balancing scale for our lives’ journeying, one threshold to another, using three luminous paintings of Johannes Vermeer as touchstones for revealing and exploring each "word picture" presented. Although the chapbook is labeled “ekphrastic prose,” and is based on A.S. Byatt’s The Matisse Stories, Tyson’s tales (short story, fiction/nonfiction hybrid, and memoir) reach beyond any label in a beautifully balanced, produced, deft, and seamless collection. The first piece, “The World Can Be Mended,” uses Vermeer’s The Lacemaker as guidance for Ashley, a medical student who spent her childhood sewing with her grandmother, but who struggles to suture expertly and quickly in surgery. In the painting, a print of which hung in her Gran’s house, a young woman bends to her lace tatting, her lemony dress lit by morning, shades of blue spilling over her intent work. “Threads gush out of the girl’s sewing cushion red as blood, the bright flow of life that courses beneath my fingers when I touch patients,” Ashley says. She longs to mirror the painting’s intensity in surgery—and must if she is to continue her degree. She ultimately finds success in an evening practice program for students. We learn of Ashley’s affair with a married visiting fellow, all part of her education in cutting the loose ends of old insecurities. In the end, a newfound strength realigns Ashley with her future, bringing her home to herself and her bright destiny. The fulcrum of the chapbook is appropriately the middle piece, “Woman Holding a Balance,” with fiction and personal memoir on either side. Vermeer’s painting of the same name is the most striking of the three in light, coloration, and layered meanings. And the piece, part fiction/part essay, appropriately holds balance in sway as the narrator Catherine questions her swirl of a business career weighed against a slower, more purposeful life. Catherine visits the painting in the National Gallery, which grounds her in “tranquility and harmony.” A woman stands at a table holding empty scales surrounded by pearls, coins, and other valuables, bathed in golden light. A picture of great intimacy, yet change and movement as she waits for the scales to balance. In Buddhist tradition, with great change and feeling "off-balance" come growth and transformation. Catherine holds her own transformative scales, waiting for the moment of reassurance, the “vanishing point” of alignment used by Vermeer, set against her past choices, including remaining childless. Still, she understands, as we all must, that we live in ambiguity, always striving for, or living into, a balance either close at hand or just beyond. The personal voice and path of the third and last piece, “Woman in Blue,” is heartbreaking though satisfying and inevitable. The companion painting, Woman in Blue Reading a Letter, is a study in blues, diminished light, and shadow—yet glowing with equal intensity and focus. Vermeer’s wife, Catharina, is the subject, a nice twin of "Catherine" in the previous essay. Here Tyson turns the page of love and grief, as she says, “the verso and recto of our deepest relationships.” Step by step she leads us through her husband’s sudden illness and passing in 2019. The memoir toggles between thoughts on Vermeer’s work and history and her own journey of caregiving and anguished parting. Again we see stillness and change—both in Catharina and in Tyson’s unreal reality. Again we are called to the everyday, the domestic, the inner world weighing the balance of togetherness and loss seemingly in the blink of an eye. We cannot restore the past, nor repair our brokenness in it. We can only navigate the rutted road ahead with as much balance as possible, righting ourselves within ourselves, through darkness and into the brighter coming day. ** Interview Questions Linda Parsons: Did you envision the three pieces as a whole from the start (the chapbook is based on a similar concept), or did it take shape over time? Gail Tyson: The desire was there from the beginning, but a different inspiration triggered each piece. For “The World Can Be Mended,” I ran across an article in The Guardian about a London event where medical professionals and knitters swapped stitching skills. It triggered personal associations and gave me a way into writing about Vermeer’s The Lacemaker. The contemplation of art inspires much of my writing, but Vermeer’s portraits of women—and the essential mystery at the heart of these portraits—speak to the mystery of being human. Linda Parsons: You beautifully integrate history and research of larger aspects, such as Vermeer’s glazing and pigmenting techniques, into the pieces without straying from your focus. What advice might you give to readers about this? Gail Tyson: Writer/teacher Priscilla Long taught me that every subject should have a hundred words. I keep my “word-trap” lists in mini-Moleskin books. Combine both sensory and concrete words, and let wordplay show you unexpected connections. When I wrote “Dark Spirits” (Appalachian Heritage, Winter 2018) about drinking whiskey with a friend who later died, I made rhyming lists—proof, hooch, tumor; distill, Tennessee hills, kill—that kindled connections. Research can easily lead me down many rabbit trails. I try to balance all that fascinating information with feeling. The fact that Vermeer used lapis lazuli more than any other painter naturally raised the question, for me, of what that did to his family budget. Expect that much of the research won’t make its way into the final work. What you choose to include or discard helps give your piece a voice. As Priscilla says, “Voice is articulated through extreme accuracy.” I’m also a huge etymology fan. The history of a word can open up an entire subject. Linda Parsons: Was the book an instrument of healing for you, and how would you express that aspect to your readers? The individual pieces each address a major turn in my life. Patty Loveless sings about seeing “what it is I can live with and without” (“The Last Thing on My Mind”). Gail Tyson: The individual pieces each address a major turn in my life. Patty Loveless sings about seeing “what it is I can live with and without” (“The Last Thing on My Mind”). Writing helps me begin to answer that for myself. These pieces also explore threshold experiences—identity, trust, loss—that everyone faces at some point. I began writing “Woman in Blue” just before my husband’s diagnosis, and after he died the writing gave me a safe container to relive unbearable pain, as well as to honour it. Only when Christine Cote at Shanti Arts Publishing decided to publish the chapbook did I see how the stories reflect the maiden/matron/crone phases of womanhood. Linda Parsons Linda Parsons is the poetry editor for Madville Publishing and reviews editor for Pine Mountain Sand & Gravel. She is copy editor for Chapter 16, the literary website of Humanities Tennessee. Widely published, her fifth poetry collection is Candescent (Iris Press, 2019).

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|