|

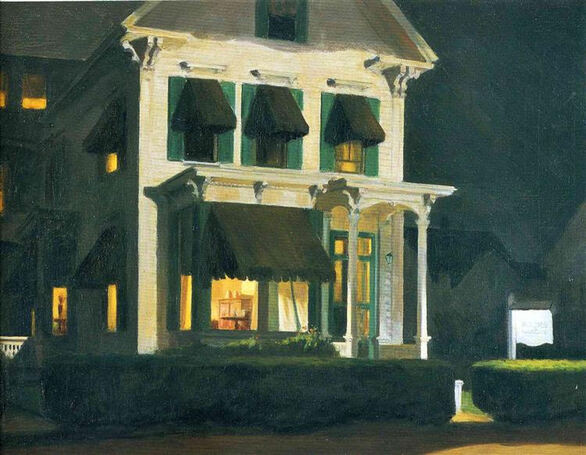

Ghost-Dog Walk with Sadie Through Edward Hopper’s Rooms for Tourists I join the ghost of my white German shepherd on the sidewalk facing the boarding house. Sadie asks if I’ve finished reading about deadly creatures. Says she could have told me magpies dive-bomb red-haired women for sport. That the ancestors of wolves hear and smell time. Behind us, the entrance to the inn pales in the moonlight. This past month, Sadie shadowed a Crescent City PI who ordered Dr. Pepper at a rural Louisiana roadhouse only to awaken in the small hours to rave about rum-and-bourbon nightmares. I was reading the history of pinball then. Above us, three rooms cast darkness across the quiet street. No one moves behind the yellow glow of the rooms that are lit. A bookshelf in the vestibule appears empty. Sadie leans against my thigh and sighs. I knuckle the length of her nose and caress the skin behind her ears. She remembers being thirsty. After crossing to a Sinclair station with a brontosaurus surviving on its roof, I buy her a Cherry Coke from a pop machine. An effervescence I cup in my hands. Upon drawing closer again to the hotel, we hear a tinny radio. Its rhythms too low for my imperfect ears. “William Bell,” she says. “You Don’t Miss Your Water.” We finish the soda as the broadcast ends. I pretend to throw a Kong into the recesses of the village. She feints toward the ruse. Then tugs at the toy in my hand before lying beside me “Read about elephants that dance to Good Morning Fire Eater,” Sadie adds. “Or Night Figures. Learn how dogs feel when their companions return from a year abroad.” I nod, listening for the songs the voiceless sing. Ghost-Dog Walk with Sadie Through Vincent Van Gogh’s Wheatfield with Crows Sadie rolls in the chaff along the trail between golden rustlings of wheat. I rub the length of her stomach, lingering to soothe the tendons that join her front feet to her shoulders. Above us, crows caw and crave. Her coat is a chiaroscuro of ermine, ivory, and Arctic polar. As if she had wintered with someone with a knack for identifying the scents of snow. Sadie hesitates before standing, inhaling the musk rising from the ground, the Earth’s memories of the first wolf family, the origin of white bisons, the last flight of passenger pigeons. Tufts of hair hang off her thighs as her molt approaches. We always visit at twilight. She always chooses our season for its warmth. As we walk, I tell her of reading a poem about the final departure of animals, of how loneliness slips into my spirit more like a homecoming than a trespass. But she keeps her mysteries still as she did while she graced my life. Around our path the crows disappear among the golden grain or into roosts secreted beyond this field. In the year of “I Wish You Were Here,” I spoke for the last time with a woman who wore sandalwood of Maurice White’s joyous vocals on “September” and of Rollo May’s Love and Will. About repertoire of fumblesome kisses. All while the doves nesting in St. Mary’s belfry ascended with the evening’s Angelus, The sun silvered the dove’s breasts until only shadows within shadows remained. In the wheat field the ghost of my German shepherd noses my wrists. On nights like this, she remains silent. And I babble about the Grievous Angel or a salad I once enjoyed made of beets, black olives, and cherry tomatoes. I repeat the long-winded parables only I understand. Sadie prances beside me. Relishing the pleasures of the body she once inhabited. Our nod to each other an agreement to hike through the night. Ghost-Dog Walk with Sadie Through Vincent Van Gogh’s Cafe Terrace at Night Sadie wiggles her shepherd body under one of the golden chairs just off the orange carpet farthest from the entrance to the café. I lean over the table, debating whether to read Fathers and Sons or Requiem for the Orchard, with de la Paz’ poem about growing up in a small town. Sadie reminds me that our sitting outside of this diner, bordered by cobbled streets, is an al fresco experience. She rests her head on top of my shoes. A wedding party approaches from the opposite end of the boulevard while the hostess distributes menus decorated with fancy filigrees. As a boy in Connersville, I had to walk everywhere I went. To the fairground beside the high school drive-in where I shoveled elephant dung. To the insulation plant where the foremen fired me for being a hippy. To the house of the only hometown girl I would ever ask for a date. The first time I sat behind the wheel of a car was my first day in drivers’ ed. A sixteen-year old who couldn’t locate the ignition switch, even though my best friend had left the keys dangling as a clue. Around us on the night terrace, the closed stores across from the café have assembled the same palette of blue that Sadie and I recall from our travels with the man with the blue guitar. Sadie investigates the scents left by the ghost-dogs that have preceded her across the years among these blue and gold shadows. In the sky, the stars resemble halos and the balcony seats above the café are always empty. Sadie asks if I’ve chosen between the tragedies visited upon fathers and sons and the poetry of working in an orchard. Given a choice, she would nudge me toward poems of joy and gratitude. Nye’s “Gate A-4.” Gay’s “Ode to Sleeping in My Clothes.” The neighbours in the arrondissements above the shops murmur l’amour through their open windows. Until someone begins singing “La Vie en Rose,” as if bouquets were serenading the evening. The very flowers the waitress removed before Sadie and I took up our stations at this distant table with its clean, white surface and one leg, a touch off-kilter when jostled by Sadie’s realignment at my feet. Nearby a baker withdraws a rafter of pistachio croissants from an oven. And the wedding couple arises to salute the revelers who have caroused with them ever since their sacrament was consecrated. In Connersville, a country singer once angled for catfish in the White River and gave the $7.80 he earned from passing the hat in a diner after singing “Your Cheatin’ Heart” and “Wildwood Flower” to a pregnant waitress to pay her rent. I bought a sausage-and-egg sandwich at that restaurant before passing my newspaper route for the last time. Sadie drops a pinwheel she has scavenged from the alley into my lap. I whistle at the spinner while she bows and wags her tail. Behind us, the newlyweds toast the waitress as she serves them a last carafe of wine. When Sadie adds her voice to the evening ode, even the fragrance from the pâtrisserie joins in. Michael Brockley Michael Brockley is a retired school psychologist who lives in Muncie, Indiana. During his career, he gathered a collection of 800 conversational neckties which he wore to commemorate birthdays, historical and humourous events, and pertinent national (and international) days. Brockley now has a collection of 80 or so aloha shirts. His poems have appeared in Gargoyle, Lost Pilots Lit, and The Whiskey Mule Diner Anthology.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|