|

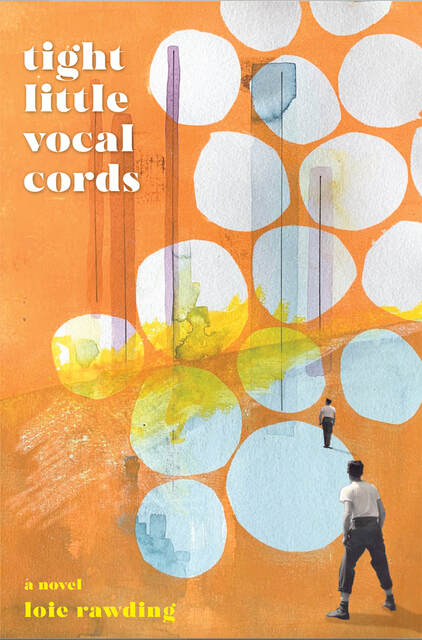

Tight Little Vocal Cords: The Ekphrastic Review Interviews Loie Rawding The Ekphrastic Review was thrilled to talk to author Loie Rawding about her gorgeous novel, Tight Little Vocal Cords, inspired by the life of American artist Marsden Hartley. Lorette C. Luzajic/The Ekphrastic Review: What was it about Marsden Hartley that inspired you to write a novel? When were you first drawn to his artwork or his life, and how did your relationship with him evolve to this point? Loie Rawding: It was early summer in 2014, when I stumbled across an article in the New York Times called “Out of Berlin, the Heart of an Artist.” This piece was announcing an exhibit that would, reportedly, leave no doubt to Hartley’s rightful place in the inner circle of American modernists. I had never heard of Hartley even as I was entrenched in my own love-affair with his peers: Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, Katharine Rhoades, and the literary artists Gertrude Stein, Jean Toomer, Djuan Barnes, and Zora Neale Hurston. These were my truth tellers and the voices, both visual and linguistic, that haunted me. And then here’s Hartley, a person who spent much of his life in my home state of Maine and never achieved the recognition he deserved while living, which I think a fear of any artist whether they admit it or not. He was described as a stoic; a lingering wallflower who loved pomp and parades, hungry to be at the centre of attention, but unwilling to compromise his complicated personal truths in order to get there. He took what he wanted from the movements of his time; Cubism, German Expressionism, and American Modernism weaving them together to best render his own interpretations of cultural, sexual, and emotional capacities as the Great War obliterated whatever sense of normalcy the western world thought would always be. What is interesting to me still, is that I didn’t love his work immediately. It was absolutely his story that I became quietly obsessed with. I tore this article out and stashed it away, knowing that I would need to do something with him eventually. I can’t explain it very well, but Hartley’s story rooted in me and he felt like a dear friend from that moment on. He became a piece of me that I wasn’t ready to unpack, a real person and true artist who would eventually help me face past experiences and my most pressing work. From time to time, I would scan through his catalog online and research his life, never quite ready to begin anything beyond notes and doodles. Sometime later, in the final year of my MFA in Fiction, a workshop professor asked us to write a story in conversation with a piece of art. Like ekphrasis, but not prescriptive or interpretational, rather a rendering of the visual field into language. I didn’t skip a beat, I went straight to my Hartley file and selected Portrait of a German Officer, (1914) which was made after Hartley’s lover died in the early weeks of WWI. By 2016, the story had evolved into my thesis project which became Tight Little Vocal Cords. I still don’t think I particularly like Hartley’s paintings, but I love them—as if I have no choice. Did your experience of place, growing up in Maine, provide you with a sense of intimacy with Marsden and his work? Absolutely. I was at this very early stage of identifying my artistic voice and still very resistant to the aspects of my life that were starving for attention. I would often lean on visual art for story ideas, always pushing away any sense of my truth in order to prove that I could write fiction. I kept ignoring the impacts that growing up isolated off the coast of Maine, being raised by a single mother, and the turbulence of a long family history of mental illness had on my personal and creative life. As I got more involved with Hartley, I began to recognize in my experience this privilege of rarely being told ‘No,’ but on the condition that I performed in precisely the way other people expected me to. Like Hartley, I worked very hard and felt lucky to have achieved so much despite lacking financial or familial stability. And like Hartley, at a certain point I began to realize this was at the expense of my most true self. We are both survivors in more ways than one and his work, especially after the death of his male partner in 1914, inspired in me the refusal to continue performing at the expense of my most necessary truths. He was there to lean on when I wanted to retreat from what needed to come out. He was a voice I could talk to about everything or nothing and he somehow managed to call me on my bullshit when I feel like I could trick pretty much everyone else. I think we need to hold our ghosts close for that purpose. How much poetic license did you take with his biography? What was most important for you to convey? About half way through the first draft, it became clear that this was not going to be a work of historical fiction, nor would it be an explicit imagining of Hartley’s life and art. I was writing a series of vignettes in conversation with his paintings which, at a certain point in his career, really begin to tell the story of his emotional life. So, his historical record was always going to linger in the wings but the novel takes serious departures to encompass aspects of my life, as well as many obsessive images that haunt me. At a certain point I had to listen to my characters’ demands; they were going to explore sexual fluidity, travel through time and space to encompass a historical period as if it could be our present because I began to discover so many connections between Hartley’s time and now. My main character began as ‘M’ and stayed ‘M’ as a tribute to Hartley, beyond that I still wonder how he would connect to this story if he could read it. The most important thing was to capture this unwieldy sense of curiosity and commitment to doing whatever it takes for M to pursue his truest desires; what it means to bear witness to everyday beauties and atrocities that may or may not be within his control to change, how M falls in love with himself and others and then, what consequences await him. What does the title of your novel mean to you? I went through a few titles before landing on Tight Little Vocal Cords, which was actually suggested by one of the readers from a publisher that rejected the manuscript. It comes from the third and final section of the book, “Mothers suck on the smoothest sea glass that their children sift from the rocky beaches. They seal the jagged, opaque pieces in jam jars with fresh water for the mantle of Sunday’s brunch, preserving the myths of a nature now on the run. Their smallest children beg to bring home the living snails that emerge from their sheaths to the harmonic hums of their tight little vocal cords.” It felt, somehow, very fitting that the ideal title would emerge from a rejection of the project. A very Hartley move, and very much what this project did for me in terms of confidence in my artistic process. To embrace the ways that this work was entirely mine and entirely necessary even if it might be challenging for others to want to understand. After it was brought to my attention, of course, I realized that this little phrase explains a big part of what the novel is doing. Through a chorus of “harmonic hums” I’m just sitting here trying to coax some living truth out “from their sheaths.” It’s also oddly sexual and mirrors in language how Hartley negotiated shape and line in his paintings. Tight Little Vocal Cords is not a traditional or typical novel. It is a collection of stories, vignettes, lists, dialogues, letters, sequences, and voices. It is poetry through and through. Tell us about the evolution of the collection and the structure. Did it start from a story or poems, later assembled, to become a whole, or did you plan it in advance as a series of connected impressions? Right, so it started as that short story assignment for an MFA workshop. My professor at the time ended up calling it out as a Modernist work, which validated the experimental nature of the prose and my rejection, even at that early stage, of traditional narrative. That story was largely made up of poetic lyric and hyper focused on image, in an effort produce the sounds and tastes that Hartley’s painting conjured in me. Once it was clear that M would not be satisfied with just one short story, I started collecting vignettes, essentially prose blocks, that were inspired by other Hartley paintings, family photographs I had kicking around, and my own memories. I submitted about 25 pages of this to the Tin House Summer Writers Workshop and was accepted. I had the exceptional honour of working with Victor LaValle who said two things: he wasn’t really sure what to do with this piece, and he wasn’t ready for it to be over. He told me to keep going, but in order to move forward I might benefit from a plan. What I took from this advice was that my instincts had taken me this far and now I needed to find a way to turn these images into a cohesive photo album. I sat down that afternoon and drew a story map; a jagged line across a blank page with tiny black dots and slashes marking where I thought something was going to happen, or go wrong, or perhaps where satisfaction was earned. It looked like this wild Morse Code with shorthand fragments starting to explain an order for the course of M’s choices. Morse Code would eventually become the only way that M speaks for himself in the novel and from there the epistolary and poetic verse forced their way in too. A review by Kelcey Parker Ervick says “It is a story not so much of characters as of body parts: flesh, thighs, and tongues with their own language and desires.” The sensual and physical here is not limited to sex, though- it is very much a book about places, their spirit and landscape, and about death. How do those themes connect for you in the story of the artist? Hartley lost his mother when he was a young child. He was shuffled between older siblings, his father, and other members of his extended family. He had a rather transient life which excited in him this tendency to wander not just around the country, always straddling communities it seems, but also to Europe and beyond. He found his truest heart in Berlin and then chose to return to Maine, the place of his birth, where he passed away in 1943. Like Hartley, I have always appreciated Ralph Waldo Emerson and that impassioned sense of landscape has become more and more important to me the older I get and the more pull I feel to return, with my family, to my beginnings. Locating M’s sensuality, in his body and his environments, is one way that I ask him to discover his own self-reliance, and in turn arrive at a better understanding of my own. Seeking and giving pleasure is something that our bodies can achieve, of course, but I’m also trying to explore the way our environments, objects, and memories take part this process too. The coastal Maine landscape is moody and unpredictable. It gives off this false sense of security, like you’ll be safe here but the minute you let your guard down it can turn on you. My mind and my body have adopted this mode, and I see it in Hartley too. Is this sensation unique to Maine? Yes and no, of course not, but it is in this particular landscape that Hartley’s life began and M’s roots were formed. This experiment taught me the importance of a permeable boundary between the body and the systems through which the body moves. To achieve this meant a fragmented sense of reality and granted me permission to enact a narrative outside the bounds of what was/is expected of me. What was it like for you as a writer to embody the experience of gay male sexuality? In his time, Hartley never vocally identified himself as gay. Historical record shows that his closest friends and peers knew, and perhaps the public suspected as his work expressed themes that celebrated and memorialized gay identity and love. This is an essential and deep part of what made Hartley the person he was. Shy and lonely; isolated and full of passion that he did not feel free to express outside the bounds of his canvas. My characters represent a fluid sexuality all to themselves. I don’t think I have executed this perfectly, but I have done my best to focus on precisely who M is and how he needed to slip between genders and sexual orientations over the course the novel. His truest self is achieved in the presence of The Soldier, his male lover that shows him what’s possible if M could only extract himself from the petty performance of normalcy. So, on the one hand this felt very easy and pleasurable for me because I was representing myself as much as I was discovering M and researching Hartley. I tried to focus on my character and what his journey needed to be, to locate within him the intimacies, losses and loves, failures and successes that are also my truth. I think often about Zadie Smith’s essay, “Fascinated to Presume,” in which she says “Novels are machines for falsely generating belief and they succeed or fail on that basis.” For some readers I have probably failed, but the journey to explore someone different from myself with risk and tenderness and love is essential for my craft and has helped me better understand pieces of myself. It is incomplete, I own that; and I own every ounce of complicated desire and sexual empowerment that I hope my characters achieve. Your creative work and teaching experience merge and transcend literary and visual arts as well as genres. What does the intersection of literature and art- ekphrasis- mean to you personally and professionally? Right, I’m entirely in love with experiencing the arts in a collective, essential conversation. I’m also super curious, skeptical, and distractable, which means I have a lot to negotiate. It’s certainly a consequence of being raised by a dancer and choreographer who, in that necessary effort to survive, became a housekeeper and caretaker of elders. Though we were poor and isolated, I was very lucky to find mentors in a variety of fields who never told me I couldn’t do what I want to do. They only ever told me to, “Prove it.” I think visually. I locate power in image and only then does language emerge for me. What I appreciate most, at this point, is the challenge that language puts upon me to construct a visual field in words that are in a constant state of failing. Like, how do I take this mess we’ve made of the English language and communicate something essential? For me, it has to be, to some degree, an ongoing debate with art. You know, what is art and what can it do in real world scenarios? But now, as I get older, art is not just fine paintings on a gallery wall or a dancer on stage. It is also the world around me and the ways that all of my senses engage with this world. Professionally, I can’t emphasize enough the gift of being told that the way you see the world is necessary and important. Our interests shift and slide and, often don’t know how to get out of the way. I try to teach by questioning these stifling traditional modes that we think we need to obey, and then embolden each individual’s way of seeing. But this doesn’t mean that my students should not be challenged or pressed to justify their choices. The practice of ekphrasis has taught me ways of validating an artistic argument through synthesis and being willing to change my point of view. What questions do you hope readers ask themselves after experiencing your novel? What else do you hope they take with them? When I was a kid, on the rare occasion that we’d go out to eat, I would tuck myself into the booth and set up a chemistry set of chipped ice, juice and water, sugar packets, pepper and salt, and whatever else the server would give me. I poured and sprinkled, mixed and mastered, pretending to be a mad scientist on the verge of some fantastic creation. Then, I’d take my fingers or a napkin and paint the mess across the table. I was always the last to place my order and the last to finish my meal. When I completed Tight Little Vocal Cords, this memory came to me again. At that restaurant table, the experiment was more important than the sustenance. With the help of Hartley, this project came out of me at a pivotal moment of growth. It made a lot of demands of me, just as it does of its readers. Writing this book taught me how to pursue and accomplish two things at the same time; the pleasure of experimentation and how to construct a plot that offers new ways of seeing, new ways of translating experience. I hope that in its own weird way this book does that for readers. That each turn of phrase becomes its own petite painting, part experiment and part sustenance—starting a conversation with its audience that extends beyond the page. And just like a painting, this book could not exist without an audience who is willing to ask questions and who is able to accept the effort that that entails. I will not presume to know what questions might arise, I’m just thankful if they do. ** Loie Rawding grew up on the coast of Maine. She studied dance, theatre, and writing at Emerson College (Boston) and Pace University (New York City) before earning an MFA in Fiction at the University of Colorado (Boulder). Loie is a Teaching Artist at The Porch Writers Collective and a freelance creative mentor. Her debut novel, Tight Little Vocal Cords, was published by KERNPUNKT Press in November 2020. She splits her time between Nashville, Tennessee and Portland, Maine. Find her at: www.loierawding.com.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|