|

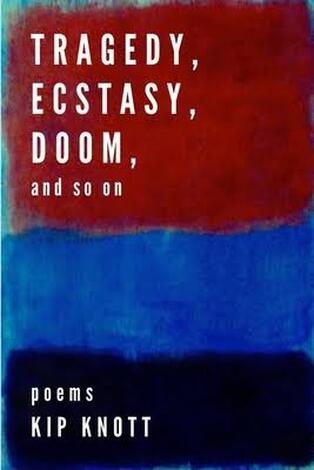

Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom, and so on, by Kip Knott Reviewed by Steve Abbott If you’ve ever noted the arresting cheerfulness of local newscasters as they segue seamlessly from murders to March Madness, you already have some of the understanding necessary to appreciate the contrasts and contradictions illuminated in Kip Knott’s Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom, and so on, recently released by Kelsay Books. It’s a thoughtful and moving set of responses to the paintings and artistic themes of Mark Rothko, using imagery that invokes Rothko’s influences—Jung, Freud, and Nietzsche (in particular, his concept of tragedy as a form of redemption)—to explore complexities of the human psyche. The book’s title comes from Rothko’s own description of his art: “I’m not interested in the relationship of color or form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on.” This collection takes those emotions and the hazy borders between them beyond its ekphrastic poems to examine the yin-yang of living: who we are, and who we think we are; what is public, and what is private (and perhaps unconscious); what is dream, and what is reality; surfaces, and what lies below them; events, and our memories of them; the differing natures of the natural and supernatural; the inescapable suffering of life, and the joy of enlightenment. As with any visual or literary art, the poems employ images that suggest light (fire, sun, moon, joy), darkness (caves, a subway tunnel, a cellar, sadness), and the unavoidable shadows in between. Less interested in answers than in probing questions, the book offers multiple opportunities for reflection. The first of Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom’s three sections, “The Biography of Fire” serves as a prelude to ekphrastic responses to Rothko’s work. It opens with “Creation Myth,” in which a dreamer “slip[s] into a hollow oak to hide” and slowly becomes part of the tree. The poem’s meshing of the human with the natural world establishes dualities where themes in Rothko’s work emerge. Anticipation and anxiety face off in “One Day,” in which the speaker “sent two letters,” one inviting that day to come quickly, the other hoping it will “take its time.” Mirrors and reflections appear throughout the collection, presenting a through-the-looking-glass dive into appearances, dreams, the real and surreal that readers will recognize. A reflection “with a hundred smiles / as sharp as the shards of the mirror he broke / one morning when he didn’t recognize his own face” surprises one narrator (“Self-Portrait in a Broken Mirror”). In “One Sunday,” the “other self” appears as a bird attacking its reflection in a window. Yet there is transcendence. By the end of this section, the speaker arrives in a clearing where looking at both the path behind and the path ahead are “the same as looking into my grave”—a sense of resolution in the present moment (“Vanishing Point”). We expect art to open our minds and senses, offering representations of, or providing insights into, the world. Nonetheless, acknowledgment of life’s pain allows for a sense of common experience that places us in the shoes of others. This collection accepts tragedy, doom and, yes, ecstasy as part of what it is to be human. These poems, like Rothko’s work, are a vehicle for self-examination. They don’t wallow in sadness and darkness; rather, they embrace them as part of being alive, tempering their impact into a larger understanding of the full range of feelings that living provides. This willingness to accept emotional darkness does not ignore that it can sometimes be overwhelming to the point of self-destruction. In “Institutional,” the poet mentions artists (Vincent Van Gogh, Kurt Cobain, Anne Sexton) who, like Rothko, ended their own lives. Even so, the poem does not succumb to despair, noting how Van Gogh’s “hollow eyes stare out into a light.” In the face of these tragic deaths, the poet affirms, “I, however, look to Van Gogh for sight” and concludes by describing himself as “a smoking wick, a small white light / glowing where purple irises bloom.” The poem, which could easily be broken into tercets, uses a beautiful repeating rhyme scheme to hold the lines—and the poet—together. In the same way, the dichotomy of light and darkness, what is visible and what isn’t, threads throughout the collection as it examines concepts that make up both art and poetry: that you can “learn to love / the absolute primary brightness of the world” (“21st Century Vesper”), and how “If you look deep into those caves, / you might find what I’m really hiding” (“Self-Portrait with a Smile”). Similarly, the difference between the public/apparent self and the inner self (what we might be “really hiding”) is reinforced as poems explore the complexities of mixed feelings. In Knott’s poems, this reaching below the surface—inside oneself—can nonetheless become redemptive rather than depressing or destructive. The centerpiece of the book, “Rothko’s Gospels” (“good news”), consists of two parts in which 19 poems respond to specific Rothko paintings, organized chronologically over a period of decades. Given Rothko’s style of composing large pieces that consist of contrasting blocks of color, classic ekphrasis—vivid description of an artwork—would not do justice to the painter’s art. Rather, the poems here exist in an emotional space divided into two sections. The first part, “The Twelve Stations of Mark Rothko,” explores how the painter’s psychological state was reflected in his artwork as it developed. Rothko’s artistic palette evolved from bright hues to darker ones that reflected his increasing willingness to examine how the personal “darkness” or “tragedy” that mark any individual’s life as just as worthy of representation in art as any other emotion or experience. The title refers to the Stations of the Cross, part of Catholic liturgy that provides meditations on the suffering that marked the Passion of Christ, and Knott uses 12 of Rothko’s works to go below the surface of things. Here is where Knott truly surprises. Offering the possibilities of both-this-and-that and either-or, these poems delve into various forms of “darkness” where light or hope unexpectedly appear. Rothko’s “III: Entrance to Subway, 1938” encounters the underworld as transformation: “the only way out is down / where something unseen… / …leads us, below // into incandescence.” Similarly, “VII. Black in Deep Red, 1957” postulates how circumstances “could be night / descending // or the morning / sun rising” or “the apocalypse blooming.” Elsewhere, “the light, though not heavenly / becomes a transitory oasis” (“X. Horizontals, White over Darks, 1961”). Throughout, the poems find hope, or the possibility of it, beyond suffering. An epigraph quoting Rothko opens “Seven Sadnesses,” the second part of the “Gospels.” It describes how each of us has our own sorrows and how the painter’s works are “places where the two sadnesses can meet.” Shared sadness is a form of healing, and this set of monologues illuminates this fact, addressing Rothko directly. One states, “Even you knew that sometimes / there is safety in numbers” (“VII. No. 4, 1964”). The comfort available in sharing griefs appears in “IV. Four Darks in Red, 1958”: “What was darkest and heaviest now floats / unrefrained above // an incandescent landscape / illuminated by a wholly unnatural light.” The poems in the collection’s third section provide other explorations of how contradictory perceptions can exist simultaneously. The three poems that conclude the book involve in Knott’s relationship with his son. The power of hope reappears as Knott explains, when his son asks if anything in the world can bring people together, that “the sky has many faces— / light and dark and shades falling / somewhere between those two absolutes.” In “Temporary Agnostic,” Knott finds momentary belief in “something / beyond this life” in “tiny bones of dandelions / clinging” to his son’s hair. The same dandelion fluff in the closing poem (“Breaking Home Ties”) captures the dualities of life in a parent’s mixed feelings as he sends a grown son off to college. The book is not without humour. Flashes of self-deprecation and irony leaven some poems with smiles of recognition. This humour includes the entirety of “Salvador Dali’s Typical Nightmare,” in which the surrealist painter finds himself a suburban professional heading to an office job in an Oldsmobile Cutlass, one more disorienting conundrum in a brand-name world. Although Kip Knott has been producing admirable work for decades and has published three noteworthy chapbooks, Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom, and so on is his first full-length collection. Its combination of skill, insight, depth, and artistic awareness makes me wonder why it has taken so long to appear and, more importantly, how long we’ll have to wait for another. Steve Abbott Steve Abbott is a former alternative press editor/writer, criminal defendant, delivery truck driver, courtroom bailiff, private investigator, information director for a social service agency, and college professor. He is founder and remains a co-host of The Poetry Forum, a weekly reading series now in its 34th year in Columbus, Ohio. He has edited two anthologies and published five chapbooks and a live CD. His full-length collection A Green Line Between Green Fields (Kattywompus Press) was released in 2018. He has never danced the macarena.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|