Premonition, by Dirk Staschke (USA). Contemporary. Premonition, by Dirk Staschke (USA). Contemporary. Lightning My museum bird pauses in the wise hypervigilance of birds, on the sculpt of a flayed arm. The arm poses, hyperrealistic, in Second Position, stretched horizontal from the missing body, hand curving down from the wrist, à la Michelangelo’s Adam, the thumbnail a postmortem lilac. Bright muscle strands shade from brick red to terra cotta to clean egg-shell tendon. Oil paint on clay, the placard says. The arm’s slick shine is that of a rubber anatomical model on a stainless steel countertop in a windowless examination room. He builds an impossible scaffolding of reasons to forgive her. He was always feeble in self-defense. Her knives were painted with butterflies. Now the world is a wall of thorns. The bird’s feet: anisodactylie—3 toes fore, 1 aft—lizard feet evolved into dainty twigs. Note: a bird is incapable of sin. No hands, no sin. He talks to birds, sucks cherry cough drops by the bag. He retreats into the softness of animals, nestles into the fur of their bellies. The arm and its bird make three shadows on the blank museum wall. The smooth-feathered flank almost breathes, the neck nearly twitches and turns, the eyes of oily black glass glisten with benevolence. He watches lightning from the rooftops, and has taken to eating sawdust in the evenings. He is the town snake-cuddler. In the long emptiness of the day he dreams he will be carried away, over fallen-down neighbourhoods, into far green fields strewn with skeletons. Ryan O’Connell Ryan O’Connell is a retired U.S. Army warrant officer, undergraduate student and apprentice writer at Portland State University. He is writing a nonfiction account of his experiences as a medevac helicopter pilot in Afghanistan.

0 Comments

Unpacking the Batik Painting When I returned from Indonesia in January of 1970, my house in Kota Belud, Sabah, Malaysia smelled musty. Mold grows quickly in North Borneo when rooms are left closed and unaired, and I had been away during almost two months of school vacation. I had completed over half of my two-year assignment as a Canadian volunteer teacher at Kota Belud’s secondary school. I really missed Rebecca, my traveling companion in Indonesian. Before flying to Singapore, I had dropped in to see her at her school in Sarawak and invited her to join me in Central Java, after her classes ended. I had been somewhat surprised by her spontaneous acceptance. I played my new Bob Dylan LPs on my little record player—“Girl from the North Country” and “Lay Lady Lay.” The songs brought back my time with her. While the music played, I unpacked and sorted my belongings. I took out the only cultural memorabilia I had collected along the way, a batik cloth painting purchased in Indonesia, which I unfolded and tacked to the living room wall. It was bright yellow-orange on a black background—more shocking than I’d remembered—with the artist’s name and date inscribed in the bottom righthand corner: “Bambongodoro Wokidjo 1969.” As I stared at the painting, the whirling ceiling fan caused it to shudder and come to life. Its intricate elements rippled, stirring up my experiences during the past few weeks. The four-legged beast at its center, lurched downward. Another beast’s head, emerging from the upper left, had cat-like whiskers and scary eyes, but both had ears like delicate butterflies. Strange fish-like creatures with ornamental tails flew in the dark sky. Detached eyes and volcano-like formations erupted in winged patterns. Streams of a blood-like lava oozed downwards. The whole scene flowed counter-clockwise, chaos emerging into a kind of symmetry; pockets of stars pulling me inwards towards black spaces of unpacked memories. *** Just a few weeks earlier, I had been lying on a straw mat on the deck of a freighter, gazing at the stars. I could see the Southern Cross near the horizon. European explorers of long ago, the first to venture into the southern hemisphere, discovered this constellation as guidance in navigating these waters, where they could no longer sight the North Star and Big Dipper. For me, as for them, it was a beacon in the night sky, inviting me southwards into the unknown. The all-Indonesian crew had fed me well and seen to my bedding needs. I only needed a sheet over me with a light blanket on standby. I grew sleepy, rocked by the waves of the South China Sea meeting the Java Sea. A warm breeze blew off Sumatra towards Borneo, enveloping me. In the morning, the sweet smell of clove-scented cigarettes woke me, almost certainly Dji-sam-soe 234, the most popular brand in Indonesia at the time. I got up to view our progress from the bow. We had left Singapore the previous morning and were now well south of the equator, bound for Tanjung Priok, the port serving Jakarta, Indonesia. As we sailed further south, I got to know the freighter’s crew. I had started to converse with them in my basic Malay the day before. Malaysian and Indonesian are derived from the same root language but some words have different meanings, providing puzzlement and humour in our exchanges. Before we reached the port, I took a group photo of the crew and exchanged addresses. They asked me where I would be staying in Jakarta. They became concerned with my answer, “Saya tidak tahu,” I don’t know. For them, only vagrants or homeless people wouldn’t know where they were going to sleep. To reassure them, I told them I had the address of a youth hostel in Jakarta, which a traveler in Singapore had recommended. The ship docked in Priok and we said our goodbyes. I walked towards a group of bemo drivers, all competing for my attention. Bemo are three-wheel scooter taxis for longer distances. I took the first one and showed my driver the hostel address. We were off with much smoke and fury, an unpleasant contrast to the pure sea air I had just left. Jakarta was a city of chaos. Driving an ordinary car through this confusion would have been a very specialized job. My bemo hit a wall of bechak, trishaws in which passengers sat in front, as if it was their duty to act as buttresses to oncoming traffic. When I arrived at the youth hostel, I met a student, Jamil, a handsome guy in his early twenties. He introduced me to Jamsudin, the more senior of the two. I couldn’t really figure out who owned the facility or how it ran. They didn’t have a register; in fact, they didn’t assign a specific room to me. I don’t recall meeting any other guests, but when I asked them where I could sleep, I was taken to a poorly-screened verandah at the back, where they showed me an old wooden door resting on two sawhorses. I was careful not to show any disappointment; after all, how could a poor traveler look such “gift horses” in the mouth? They didn’t provide a mattress, not even a pad, nor a mosquito net. At least I would be dry in case of rain, I thought to myself. In the evening, we went out together to a night market for some curry and rice. The market was filthy, garbage strewn all around. I was sure I would get diarrhea from this hospitality but I felt compelled to accompany my friendly hosts. I probed a bit into what it was they did, what they were studying, and where they came from in Indonesia. They told me they were both from Jakarta, itself, but remained vague about their activities. They briefly mentioned the 1965-66 right-wing coup and revolution the country had gone through, but I couldn’t figure out their opinion of or role in this upheaval. After eating, we wandered through the streets and they took me to a one-story house surrounded by a wall. It was full of young Indonesian girls. At first, I thought they were sisters or cousins. We joked and laughed and drank some beer with them and the older “aunty” who was present. We sat on some plastic chairs in the outside hard dirt compound and passed around a joint of marijuana, called ganja. I got a little high. In spite of my state, or perhaps due to my increased acuity, I soon realized it was a brothel and that I was being matched with one of the “sisters.” She was just as attractive as I was sexually frustrated. Besides, I felt I couldn’t refuse my new friends’ hospitality, lest I offend. Jamil and Jamsudin also went off to separate rooms with a couple of girls. It seemed like they were just following a frequent pattern. Making love with this girl was mechanical and unfulfilling. It was over in a minute and I was out of there. As I emerged, I immediately regretted it. The brothel didn’t have any condoms and I wasn’t prepared. I knew I could get gonorrhoea or some other sexually-transmitted disease from this encounter. I can’t remember who paid—probably my new friends. My own payment was yet to come. When we returned to the hostel, I told Jamsudin and Jamil that I was tired and would go to sleep. Jamil casually said, “You’re safe with us.” In unison they suddenly brandished their pistols, grinning ear to ear. Alarm bells rang in my brain. What had I gotten into with these guys? I could have kicked myself for being so naïve. Most law-abiding people didn’t own handguns in Malaysia or Canada, and I doubted if they were allowed in Indonesia. Since it was too late to find other accommodation and probably too dangerous to go out alone in the dark, I kept my cool and went to my “room and board.” That night, different scenarios darted around in my head as I drifted in a state of semi-consciousness with the sounds of Jakarta traffic, the scuffles of distant dogs, and the drone of mosquitoes penetrating the warm, polluted air. Towards dawn, roosters warned me more than thrice. Signs of my impending doom? At the time, open wounds remained on the land and Indonesia’s psyche. Only three years had passed since a band of rightwing generals had overthrown President Sukarno’s nationalist government. With the help of the CIA and State Department, the American military had educated and trained these rebels who were led by General Suharto. He had taken over as President. Clearly, Sukarno had been too nationalistic, too leftist, and too friendly with Communist China for American tastes in an era when the “Domino Theory” was still in vogue. Americans believed that if Vietnam was lost to Communism, the rest of Southeast Asia would follow suit. The assassination of six rightwing generals by Sukarno’s supporters in the Indonesian army led to counteraction from the right, pitting opposition parties, anti-communists, and right-wing Muslims—including militant youth groups—against the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and its national apparatus from the top down to the village level. Terrifying beasts lurched through the land. Many people were accused, rounded up by gangs, and imprisoned without trial. Between half a million to a million men, women, and children were shot, decapitated with swords, or hacked to death with long knives, called parangs. Village forces, in consort with the paramilitary Komando Aksi, executed people in a systematic way, bringing thirty to fifty victims at a time to designated places, often riverbanks, to be slaughtered like cattle or goats during the night. The rivers of Indonesia flowed with blood, body parts, and the putrid remains of corpses. Only a scourge of crickets sang about these deadly deeds. Most people remain silent to this day. In the morning, Jamil and Jamsudin offered me a breakfast consisting of egg curry with roti, a flat pan-fried bread. They seemed quite normal, with no signs of hostility or intention to harm or rob me. I didn’t know a lot about the situation in Jakarta, but I concluded there must still be active factions within the student population and their pistols were some sort of insurance. For the next couple of days, I explored the city, staying out long enough in the evening to avoid being pressured to return to their brothel. I had a few meals in a modern hotel, a little too expensive for me, but I couldn’t afford getting sick. Jakarta was a dingy, dirty, disorganized place—garbage strewn everywhere. The water in its canals moved ever so slowly through cesspools of paper, plastic bags, feces, dead animals, offal, and oil. After three nights with Jamil and Jamsudin at the student hostel, I took a morning train to Yogyakarta in Central Java, a scenic ride which cleansed my mind of the grime of Jakarta. Rebecca, coming from Sarawak via Singapore, flew into Yogyakarta airport. She was attractive, cute actually, with short dark hair and long legs—taller than most Indonesian men. She also looked fit and able to take care of herself. But at the time, it was considered unsafe for women—especially Western women—to travel alone in Indonesia. Many Indonesian men generalized from the behaviour of female film stars in Hollywood movies and assumed Western women were loose and available. Our first destination was Mount Merapi, a name which means “the one that makes fire” in old Javanese. It’s an active volcano in Central Java near the City of Yogyakarta. Merapi erupts, on average, every five years, according to records dating back to the 1500s. The last eruption had taken place five years before our visit, but we were told there would be signs if it wasn’t safe enough for us to explore with a guide. Looking down from the top of the crater, the cauldron radiated much heat and stank like rotten eggs. The boiling orange pot and shooting streams of lava reminded me of the volatility of this country. The killings in some parts of Java had only ended a year before our visit. After descending from the crater top, we took a taxi to the nearby ancient Buddhist temple complex of Borobudur. We carried a tourist brochure with us—“Borobudur Temple Compounds”—to understand the layout and history. The temple had been built during the 8th and 9th centuries C.E., after Eastern Indian traders and missionaries brought Mahayana Buddhism to the island. But volcanic eruptions had necessitated moving the seat of the empire, and gradually, the temple complex was covered by volcanic ash and then jungle, lost to memory with the coming of Islam in the 1500s. The Dutch completely unearthed it by 1835 and the work continued during our visit by the Government of Indonesia. I had purchased some ganja from Jamil in Jakarta (one of his income-generating sidelines, I concluded) and decided to bring it along for our excursion. We smoked some before we entered the temple complex, a giant hill of elaborately carved stone. Borobudur’s floor plan is like a huge mandala, a physical representation of the spiritual universe. Pure symmetry. For a couple of hours, Rebecca and I wandered in silence, feeling at peace. The stone reliefs spelled out the law of karma, the birth and life of Gautama Buddha, and his search for enlightenment, which I had studied. We progressed from kamadhatu, “the world of desires” to rupadhatu, “the world of forms,” finally arriving at arupadhatu, “the formless world.” I knew that the Buddha’s final destination was the ocean of nirvana, a pure, liberated state, void of self; however, this was the first time I had experienced these ideas without the encumbrance of analytical thought. For a couple of hours, we floated, thankfully without a guide, meandering through the many statues and stupas until nearly sunset. These experiences brought Rebecca and me closer. We talked and laughed a lot, comparing our boring North American culture to this exotic place. We sat close together while taking a bus back to our hotel in Yogyakarta. We were both hungry and went out to eat and to shop. It was then that I impulsively bought the batik painting at a local art store. It was in the shop that a new kind of “volcanic eruption” began. I had felt mild pings of pain during the day, but now the wicked beasts of gonorrhoea had come down upon me, a full-frontal attack. Rebecca and I were sharing the same hotel room, and as we exited the shop I confessed my problem to her. She was really cool about it, kind of matter of fact. I took her back to our hotel in bechak, and then told the driver to take me to a clinic. The Indonesian medical staff I met were equally cool. They knew the symptoms well—just jabbed me in the rear with a shot of penicillin, and sold me a course of penicillin pills to take for the next ten days. In the meantime, they told me to avoid sex. This was a very depressing development for a young man traveling with a beautiful woman. I knew Rebecca had another guy on her mind, but before my embarrassing situation arose, I was privately wondering if she might want to make love with me. I had really blown it. How stupid could I be? Fortunately, she didn’t express any disgust, just laughed it off. I had to become Buddha-like and quell my passions—focusing on talking and enjoying the architecture, art, food, and people of the land in which we were temporary guests. From Yogyakarta, we traveled by train to Surabaya, took a bus to Ketapang, and a quick ferry to Gilimanuk on the island of Bali. We rode on the back of a truck to Denpasar, where we stayed in a very cheap guest house on the beach. We swam and walked, searching for sea shells. Our visit took place long before major hotel chains and package tours invaded Bali. Food was very affordable and tasty; people friendly and welcoming, no hustling or pressure to buy. It was a “take it or leave it” place: “Do join us but please don’t disrupt our way of life.” The appearance of the land belied Bali’s turbulent history: Early humanoid migration followed by Austronesian peoples seeking its rich volcanic soils for their rice and fruit trees; Indian traders and missionaries; the establishment of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms; the arrival of traders from China; and centuries of domination by Javanese and Muslim sultanates. Then, in the early 1800s, and in quick succession: the Dutch alongside the French, the English, followed by the Dutch again in 1816. During the next century, the Netherlands gradually consolidated their control over the whole Indonesian archipelago, including Bali, where they fought local rulers under the pretext of controlling the smuggling of arms, opium, and slaves. Then, Japan invaded in 1942 and carried out equally brutal occupation policies. Bali, along with the rest of Indonesia, was returned to Dutch control in 1945, when the Japanese were defeated. But by then the people had suffered enough and they reignited their anti-colonial struggle in-earnest, finally gaining independence within the Republic of Indonesia in 1949. However, the island was not saved from the horror-filled, anti-communist killing spree that had decimated Java and Sumatra during the years of 1965-66. This violent history mirrored Bali’s many layers of volcanic soil. In 1963, Mount Agung had exploded after a hundred years of slumber, destroying many villages, and killing more than a thousand people. At least twenty-five significant volcanoes were still active at the time of our visit. Rebecca and I rented a motorcycle and ventured into the volcanic hinterland by day, visiting vibrant villages and Hindu temples, both old and new. People smiled and waved, including confidently bare-breasted women surrounded by multi-coloured flowers and birds, palm trees, and ferns—visions of the Garden of Eden before the fall. Children, we remarked, seemed to be everywhere—an overabundance of human fertility too. We were reluctant to leave Bali when our time was up, but boarded a flight to Singapore. I completed a large counter-clockwise circle of over 2,000 miles (3,218 km) —from Singapore to Jakarta, through Java to Bali, and back to Singapore again. By that time, I had also completed my course of penicillin and the beasts within me had been quelled. During that last night, Rebecca and I finally made love, the climax—so to speak—of a memorable, if somewhat frustrating, journey. I didn’t know then, and never found out, what her motives were. Did she feel anything more than friendship for me? Had our relationship grown to the point where she was forgetting about the other guy? Afterwards, I felt that night may have been only a reward for my role as a good traveling companion—just a pat on the back. The next day, I boarded another flight to Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, and then drove my motorcycle to Kota Belud. Rebecca had a shorter flight and bus ride to her post in Sarawak. In spite of my doubts about her, I already missed Rebecca a lot. Being so close to a woman on a similar wavelength, and then returning to my isolated town of Kota Belud, was an immediate downer. But I had to be realistic. We were based far away from each other and had our teaching assignments to finish. Letters would be our only connection. *** I woke up in my comfortable chair in Kota Belud, the batik creation before me—its beasts and the blood they sought, the volcanoes and explosions of stars. The music had stopped long ago, the needle returned to its resting place. My little bungalow was completely still. Eerie, actually. I went to bed but couldn’t sleep, feeling some panic. I got up, put on my shorts and a shirt. I slipped on my thongs, walked up the road and around the corner. Looking south, towards the solid silhouette of Mount Kinabalu, I searched the horizon for the Southern Cross but I was too far north. Other stars framed the mountain and a warm breeze coming from its direction, touched my face. I could only hear the familiar cheers of crickets and the muffled sound of water buffalo munching on grass down the road. My pulse subsided. I had returned from chaos back to symmetry. Neill McKee This story is adapted from Chapter 9 of Neill McKee’s first travel memoir, Finding Myself in Borneo, https://www.neillmckeeauthor.com/buy-the-book, which won a bronze medal in the Independent Publishers Book Awards, 2020; the New Mexico-Arizona Book Awards 2019 for non-regional Biography / Autobiography / Memoir; and a Readers' Favorite Awards 2019 in the travel book category. Neill McKee is a Canadian creative nonfiction writer based in Albuquerque, New Mexico, https://www.neillmckeeauthor.com/. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree, from the University of Calgary and a Master’s Degree in Communication from Florida State University. McKee worked internationally for 45 years, becoming an expert in the field of communication for social change. He directed and produced a number of award-winning documentary films/videos and multimedia initiatives, and has written numerous articles and books in the field of development communication. During his international career, McKee worked for Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO); Canada’s International Development Research Centre (IDRC); UNICEF; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland; Academy for Educational Development and FHI 360, Washington, DC. He worked and lived in Malaysia, Bangladesh, Kenya, Uganda, and Russia for a total of 18 years and traveled to over 80 countries on short-term assignments. In 2015, he settled in New Mexico, using his varied experiences, memories, and imagination in creative writing. The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin

In the 20 years since I brought this gift-shop print home from the Louvre, I’ve been eye to eye with a powerful early Renaissance man. His russet brown surcoat is covered in gold embroidery. He’s kneeling, on the left side of the image, at a lushly draped prie-dieu, his graceful fingers pressed reverently palm to palm, an attitude of prayer. Below those folded hands I see an illuminated book of prayers, more evidence of wealthy piety. There’s nothing just “off the shelf” in this man’s world. As I sit at my desk, his picture hangs to the right of me. To my left, my third-floor windows present a background of sky and a foreground of American elms, centenarians taller than my house. Sometimes the trees and sky are just what I need: visual respite for computer-tired eyes. Varieties of green in summer or branches loaded with blizzard-dropped snow. All seasons, the rich guy waits patiently for me to look his way. In the other half of the foreground, a richly-clad Virgin holds the Christ Child on her lap. Above and behind her, a hovering angel (with rainbow-coloured wings) holds an elaborately jeweled crown. The Virgin looks down, not out, as if aware that her function here is as a throne for the child on her knees, who holds a crystal orb crowned with a jeweled cross. That child has both an old man’s face and a chubby baby’s body. He is King of the World, the orb shows, but he holds it in a plump baby hand, his arm supported partly by his mother’s light grasp. His wise old gaze is turned to the kneeling man, and his other hand is raised in blessing. The man does not look back at him. I do not turn deliberately toward this image, (or I didn’t in the early days) but I sweep my eyes over it, when I’m moving right to change my music or maybe when I tilt back my chair and catch his eye. And then I’m gone, deep into the details. I’m drawn like a magnet into his face, his world and I forget about time. Three human beings occupy that foreground, but only one of them looks in my direction. Only one shows a countenance that is not fully confident of what’s being re-enacted here. The Virgin and Child have their tasks and they have completed them. Mother and child share a common complexion, a light blush across the cheeks. Only the man looks askew, with a weathered countenance. The nose, the upper lip, the cheek all are roughened red. By shaving, by weather, by living. The dark pool of his right eye (because of the angle, the only one visible) does not reflect light. It is a dark pool, matching the darkness of his hair. I can’t decide if I would like to sit across a table from him or would fear his power. His slightly turned head seems to jut out of the flat surface plane. The artist’s oils play up the skin surface, the vein descending from his temple, the furrow between his brows, that slightly sagging jowl line meeting the folds in his neck. That face, with its cragged determined particularity, and the lighter colour of its skin, stands out against both the dark and patterned space of the foreground (the checkered floor, the carved capitals) and the open sky, buildings, fields and vineyards, seen through the arches that open outward behind him. His costume and surroundings proclaim his wealth, but the face says it hasn’t been easy. Over and over, the textures and patterning and above all the face, draw me in. No monkey mind can escape the power of this meditative object. Stay still, look. And look again. I go back to his face, that human being, I can’t figure out that face. Something surges beneath the surface. Pain, pride, determination, steely reserve? In life, we often think we know a great deal about people whom we frequently see. The man is more like a fellow CTA passenger with a face that shouts, “Story here!” We have only a few stops and with a safe angle for viewing, we start guessing. And then the person’s out the door. This commuter, the one on my wall, never exits. Recently, thinking to deepen my meditation by learning more about the painting, I went surfing for more knowledge. Then, I discovered my mistake. I searched for “Memling,” “Virgin and Donor” and found nothing. Jan van Eyck, not Memling, painted this image and the man is Chancellor Rolin, a powerful figure at the 15th century court of Philip III of Burgundy. At age 60, the Chancellor commissioned this portrait for his parish church in Autun. It now hangs in the Louvre. How I made that mistake is another story. What’s important here is that the image’s ekphrastic power over me came from the image, came not from what I knew but what I saw. I love the agile, dancing smartness of art historians but I didn’t need it. For 20 years I have been free to follow my own thoughts, to begin sentences with “I,” to meditate on how difficult it is to know another human being, or on how far apart divine and human spheres are, even when painted into the very same room. I was freed from pondering the embroidered border of the Virgin’s robe or the Angel’s wings. I am not scrambling for glory in an art historical world. I gaze, I fall deep into the details, and I am freed from time and space, from the “I” of my self. Chancellor Rolin is still on my wall, waiting for me. (“The Chancellor” is better than “the rich guy,” so that’s a plus.) I hope we have many more years before us, eye to eye. Next summer, I’ve scheduled a visit to Paris, to see the Chancellor again, up close. Mary Harris Russell Mary Harris Russell, a retired English professor, lives in Chicago, meets regularly with memoir writers and, though she does not sail, has an app for the Beaufort Wind Scale on her phone. NB: The author believed this print to be from Hans Memling (15th century, Flemish). The painting is called The Madonna of Chancellor Rolin (or, The Virgin of Chancellor Rolin), by Jan van Eyck (Netherlands). circa 1435. West Wind

I. She’s a smudge, although she doesn’t know it; doesn’t see enough of her surroundings to know she blends in to them: sage and brush brown, her skin obscured, eyes dim from the cold. If she knew, she would paint herself red in heather berries, soak her clothes in mulberry dye, dip her arms in up to the elbow before she went out into the world on the edge of a storm. She doesn’t know. Why would she need to be seen? II. It’s the height that she doesn’t understand, the rain only baffles her as it comes on sideways and sharp. And the purple above the cloudline twists her stomach, so she doesn’t look up. She would worship older gods if it weren’t too late. She would become them in one motion, like the grasses and the buffeted flaps of her clothing. She would become. If only she knew how to. III. A woman carries a basket of berries across the heather, looking out at the roaring maw of the sky in apprehension. She must remind me of cave drawings, the way I am drawn to her, sculptures that were brown-wood and womanhood, carved by men in their free time, unaware that years later it would be art, and they would be artists; years later and the sepia of her common dress (and arm and hat and basket) would remind me of them. That their art had become self-aware. IV. She would bleed into the sky if I let her, her pigment twisted by wind shown only by brushstrokes, her definition lost, her gale-swept outline now infinite, growing. Become cloud, become rain, become wind, become the colors of the heavens before a storm: purple, grey, sepia. V. Does she know she’s on the edge of the world? Does she know that the sky might be white or blue or midnight green somewhere else? Like when yesterday on the bus I complained about the darkness of early afternoon in winter, and Sarah told me all the places it was early morning at that exact moment, which helped. Therapy is imagining the theoretical and accepting it as reality. Therapy is standing in the sun on purpose, or searching out all the non-existent colours in the sky, or looking at brushstrokes that trick the mind into imagining the concept of wind. Norah Brady Norah Brady is a fifteen year old poet, actor, and wanna-be author. She’s most at home anywhere she can write, preferably with two cats and quite a few books. You can find her work in Rookie magazine, The Blue Marble Review, and Write the World’s 2017 collection: Young Voices Across the Globe. On Hockney

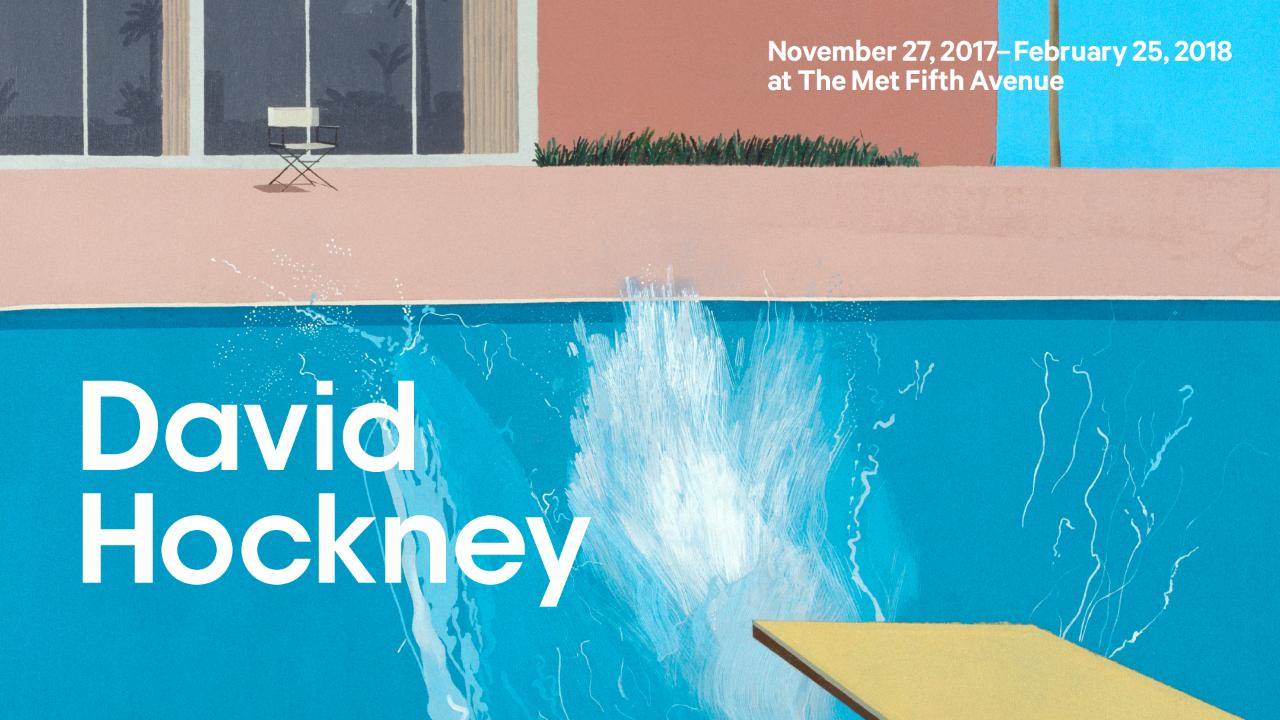

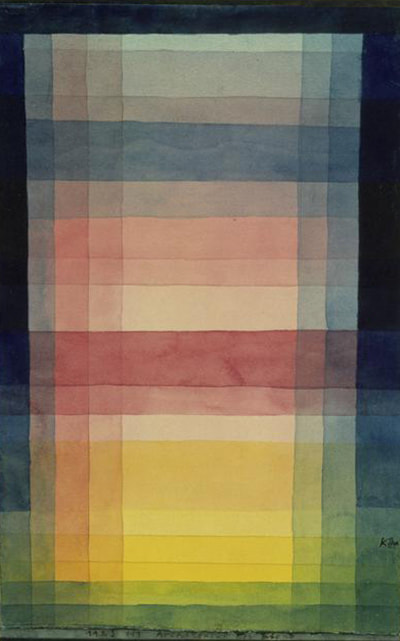

x. What story do we tell the mirror? Do we sing it love songs or deliver it an essay, dry and annotated, sober and coherent? My mirror is tall. My mirror is wide and long; it has untold depths. See, sometimes you can look in the mirror and see a face that’s not yours, or a face that was yours. You can, in a mirror, see behind yourself in ways otherwise impossible or very — highly, you see — unlikely. There is synchronicity in our reflections; yours looks to be yours just as mine appears to be mine. x. I am slowly becoming better at looking at myself. x. The story of the mirror is the story of myself inverted. I was the first and third born. I never left home and there are no windows in my childhood bedroom, in fact, there are no windows anywhere in my life. x. The mirror and the window play prominent roles in the work of one of David Hockney. David Hockney and voyeurism are me and voyeurism, are me and my substances, are me and my self when under the influence of love and leering eyes. They addict (they yearn) for a subject; the subject is everything and empty. Hockney and reflection are the heart of the matter, something like a raison d’etre, and he has introduced us all to the colourful yet monochromatic, the blurry yet separated, the balanced yet falling apart, the single sourced, the placid, the mysterious, the awake and daydreaming. He has explicated to us our culture's concept of calming down, and, vitally, ideas of what success really felt like for affluent white cosmopolitans. A riff, a portrait of his portraits: affluent white cosmopolitans: queered and pastel, permitted and flaunting, flat and flaccid, naked and bitter, fists dripping in anger, glass jaws supporting eyes in a directed gaze, (panelled portraits of these orchestrated gays), moments extended, the glance here lengthened into a piece of unchanging, static art. It is the opposite of animal and is animal. These are charged instances rubbed down, reanimated, forgotten again, then made to emerge as a moment and a memory of a moment. They have history and future, they tease the surreal (they mock it really); they own sex (they unown sex), and, accordingly, hold each of us accountable. His work cares nothing for you and his subjects care for nothing. Someone, namely Hockney, discovered for us the beauty (could you call something pink and teal profound?) in the vapid, the depth that rests in our peering vacuous eyes. Someone, namely Hockney, discovered for us the beauty in the elevated, the depth that rests in the shimmering that makes us up. x. We are all visitors to and with one another. We pass through each other’s lives like sunlight through sun-facing windows; we take some things and we leave others. In our wake are scars and marks and bruises and pain but also warmth. Our compensation is constituted by lessons and diatribes and ideas and ideals. We move often in tandem but are always approaching a point of divergence, a split in our paths, and this is good, is okay, is natural, is true. As I reflect on a Hockney from my history — a piece that is only still somewhat with me, a piece with three planes and three mirrors and a single light source — I am reminded about the days when I would dance in front of my twin brother’s mirror, naked, the opposite of hirsute, dangling, passionate, a wannabe Hockney subject without those words to know it, addicted. Was what I saw a little boy or a fierce subject, and did that mirror lie to me as a gym scale lies, was it tall, wide, with untold depths? x. My roommate is surely at home, staring in our very tall mirror. The reflection in the mirror is not whole; the person you are (and the person you are with) does not exist in full; we get fragments, only, of each other and we construct around these fragments ideas of people, of personhood. Varyingly: we lionize and we ridicule. As people round out, as they became more to us, we are compelled or repelled; are drawn in or drawn out. This is the getting to know phase. Hockney is benevolent: he allows us, in his figures, to see the shapes that form their foundations. The cubes and rectangles and spheres and ovals that compose us, our personhood, our bodies, them and their bodies. Our skin and the bones on which they are tendonly grafted are brought forth in his work. What happens when we get close to people, when we “open up” to them, is it that we are displaying to them the shapes that form what we think (and therefore actualize and know) to be our selves. There is a beautiful geometry to the manner in which we become intimate, how the slope of shoulder meets the curves of neck, how what we share and what we express and what we are fit snugly next to one another such that we become a composition. And in these Hockney subjects that geometry can be undone, and then may only be suspended in the moment that is captured in the work. Remember: Hockney has left hours of canvas undisturbed, as the spaces that are inconsequential to the geometry of our lives are not his concern, or, make up a different composition, still an elegant, lively geometry but blind to the subjects at hand. x. A triangle resides between us; its three points: the voyeur, the representative, and the reflection. Maybe this triangle extends and envelopes us, is a fence or a boundary, a law in which we are stuck and subject to. We slip from corner to corner; at times (at certain points) we cower and crouch and nestle up so closely to the walls of this structure that we forget they exist or can be transcended and escaped. This triangle is a pool suspended in splash. Is a swimmer submerged and unmoving, glanced down upon by a wealthy white cosmopolitan, whose blonde hair holds more volume than the rolling LA hills behind him. Hockney has, absolutely — unbelievably — discovered a depth and heart to the spoils of high society, that is, frankly, repulsive, that imagines it is everything and is in fact nothing and perhaps operate as a net-negative. But he’s discovered something, and it is moving. x. There is reflection surrounding us, chasing us. It sits (so charged) everywhere; it glances about every which way and it has, always, something to say. Life is but a collection of mirrors and windows and spit-shined marble and plastic-fake leather patterned with our reflected faces and there is nothing we can do about it. x. Hockney painted from postcards and nature magazines. His reflections are repurposed reproductions of images and stills and worlds and landscapes that may or may not have existed: there is value in the intangibility here: what is abstracted more than once is then again a real object unto itself. x. How do we avoid writing, even in brief, about Hockney; I am flummoxed. x. A third device in Hockney’s work is a confluence of the first two: the swimming pool. Both reflecting and allowing our sight to pass through; both distorting and revealing; both deep (owning depth) and immaculately flat. x. I had great difficulty getting dressed today, this morning. Maybe it was a hangover debilitating my tastes and confidences. Or perhaps it was my capricious mirror that kept rejecting my humble attempts. Perhaps, more, it was Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist telling me to do better because the issue pestering me was one of texture: how to complement different fabrics in my clothing; the (utter and urgent) importance of flatness as juxtaposed by depth, of cotton flouting wool, of soft sitting under (and distinguishing itself from) an overly starched collar. The shapes that make up the whole, my geometry I am getting to know but, now post-Hockney, may be my unbecoming. x. Beefcake magazines and hypnotists; swimming pools and suspensions of emotion. I had a beefcake magazine, a shrink, the image of a swimming pool and suspended emotions, and I fantasized - inspidly, unknowingly - about being a Hockney subject. x. Voyeurism, but consensual: telling someone that you want to (erotically) watch them from afar and having them in reply nod and say okay, alright, what do you want me to do? To establish intimacy via distance, ignoring fingertips in favor of eyelashes, to be within someone but only via their lingering awareness of your gaze. x. Hockney cashes checks on the fact that we all want to be there, at the pool, shirt off, carefree. He reveals that all of us: we wish to be watched. x. Remember my quest to see myself better? Remember that the mirror inverts my history and the type of blood that flows through me and, even, sets its own course, even, establishes addictions. I wish to be watched and I wish to imbue intimacy. We wish to be watched. The genie in its shiny bronze lamp (maybe this lamp is aquamarine and resting in the bottom of a swimming pool nestled into the winding LA hills) announces itself (bright blue) and grants you three wishes. You, desperate, use two of them to be watched: first by Hockney, of course, and then by the rest of the world. You hold onto your third wish closely, having slipped it into your chest pocket, you pat it as you pass through doors, as you peer out windows, as strangers bump into you on the subway. One day it will come of great use and the whole world, Hockney (emphatically) included will be witness. x. In Hockey, one can always count the plains — do it yourself it’s fun and will impress your friends — but they are there to establish the space between you and these lives, which is exclusive and imperious, yet generous. It’s a warning, not an invitation, though it’s seductive, as these things are. Most good art warns you in some manner. Compels you away from something you now know (perhaps have long known) to be unseemly, to be unjust and unattractive. Hockney, in his mysterious, is generous. x. If Hockney painted a park in New York City it would not be one in Queens or Staten Island (though they have a great many parks, a great many sights and peoples) but, rather, it would (certainly) be either the southwest corner of Central Park (Columbus Circle) or Washington Sq: the lush greens preserved yet set aside, the concrete within and above and surrounding, the stone smooth and there to sit on and photograph (but maybe only for people of certain tastes), the dirt kicked up and stuck within shoes, a place of activity for those that wish to be like a Hockney, watched and quietly violent. But we prevaricate and are soon to return to the park, not a park, but the park, where we will together and in tandem, in perfect harmony, watch the people as they move about. Aron Canter and Holden Taylor Aron Canter and Holden Taylor collaboratively write essays off a single word document, so the essays are a document of performance as much as a realized piece of non-fiction. Their interest range from syntax and language, to criticism and humour, to impact and meditation. The Snail My father would use the salty brine from the olive jar as salad dressing, pouring it until a little pool formed at the bottom of his bowl, lettuce leaves ever so slightly swirling, like the dream I had last night where a snail circled softly around a pile of salt, but it did not melt, just climbed higher, and when I called to him to look he walked away, jangling the keys that dangled from the balloon-shaped leather keychain he used to hang on a hook by the front door of the army base house we lived in when I was four, where once I saw a real snail on our wide concrete sidewalk and crouched down low beneath the hot Oklahoma sun and watched it drag its slime across the shadow of my hair while my father started up the Volkswagon, his cigarette smoke swirling patiently from the window. Amie E. Reilly Amie E. Reilly is an adjunct professor in the English department at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut, where she lives with her husband and ten-year-old son. Her most recent work can be found at Fiction Advocate, The New Engagement, The Evansville Review, and Entropy. She also blogs at https://theshapeofme.blog/. Go Back to Finger Painting Remember the smeary freedom and tactile bliss? How you could fill the page as it curled with fire and became uniquely yours, yellow never just yellow and red never lonely red. The fluidity of identities, a meld of hues and primaries, of places, lands and waters crossed, capsized emotions. Light and its absence, the greatest sorrows, fragmented and unpredictable. By the time you finger your colour it’s already changed. Take Klee whose watercolours shift according to your gaze. His Architecture of the Plain depends on conjecture. Some days deliver its pleasing synchronicity – darker blues and greens defining margins left and right – and the coloured rectangles overlap, now raspberry, now vermillion. Fleeting moments pass and all you see is collision, hear a noisy argument, colours clamouring for space. Klee knew what he was doing – flat as a checked shirt pressed on an ironing board, yet there’s such depth to the painting, you want to put your hand through the paper and feel around, you want to wear your shades, tag your name graffiti-style to the lowest rainbow stripe. This is a multicoloured manifesto of love. Darkness and light in perfect Greek proportionality, an artful construction based on math and spontaneity where form is all there without being too visible. Look carefully: the ratio of the smaller part (the yellows, say) to the larger part (the reds) equals the ratio of the larger part to the entirety (the painting). Even your fleeting childhood, even your fingers painting reflect a perfect symmetry where yellow is to red equals red is to (yellow plus red). See what I mean? The painting is greater than the sum of its brushstrokes. Cora Siré Cora Siré is the author of three books. Her latest novel, Behold Things Beautiful, was a finalist for the Quebec Writers’ Federation Paragraphe Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction in 2017. Her poetry, short stories and essays have appeared in many anthologies and in magazines such as Arc Poetry, Literary Review of Canada, Geist, The Puritan, carte blanche and Montreal Serai. Based in Montréal, she often writes of elsewheres drawing on her encounters in faraway places and her family’s history of displacement. For details, please visit her website, www.quena.ca. Millennia Insecta I have known the eons-long longing of insects gone to stone, the empty wishes of disjointed plates no longer encasing throbbing thorax, fecund abdomen, the despondency of coxae that once cupped flexing femurs, the weariness of wings become limestone lithographs, the layered years hardened against weather: sturdy siltstone, kiln-baked mudstone that hold the compressed millennia of wisps of beings that whisked the air mere days, then died. And I have seen a day pass from horizon to horizon in the instant I looked up from stone to sky, the split second I became aware of buzzing and flapping around me, the flicking wings, the whirring flags of chitin and scales, the jumping, hopping, stalking, searching, pulsating life arisen from these very foundations of their world. Roy J. Beckemeyer Roy J. Beckemeyer is a retired engineer and scientific journal editor who lives in Wichita, Kansas. He currently studies the Paleozoic insect fossils of Alabama, Kansas, and Oklahoma, and writes poetry. His poems have appeared in half a dozen anthologies as well as in many print and on-line literary journals. His first book of poetry, Music I Once Could Dance To (Coal City Press, Lawrence, KS, 2014) was selected as a 2015 Kansas Notable Book. He won the Beecher’s Magazine poetry contest in 2014, and the Kansas Voices poetry award in 2016. He recently co-edited (with Caryn Mirriam-Goldberg) Kansas Time+Place: An Anthology of Heartland Poetry (Little Balkans Press, Pittsburg, KS, 2017). Girl on the Beach, 1957

You can’t judge sugar by looking at the cane — Willie Dixon When the canvas was white before its “pristine surface was besmirched,” the artist must have imagined he lived in an occupied country run by a puppet government. Centuries after Vermeer took a boat ride from Delft to Leyden, picturing not a secular madonna but the narrative possibilities in a woman crying by the river, Diebenkorn painted a figure into the layered impasto of sand—transformed it into Girl on the Beach. I wonder that she’s so far from the centre. I’d guess she’s half a mile from the almost black Pacific, thin ribbon below broader ribboned blue-cracked sky. Strangely, I’ve always been attracted by the centre. Something about its vocabulary, how it offers a canopy to the surrounding architecture. The girl, who simultaneously appears both defiant and buoyant, reminds me of mating elephant seals drawing blood in Drake’s Bay or the wary Tule elk of Tomales Point. Thick strokes conjure orchid petals. One or more of her parents must be multi-floral. The painting’s odour is tropical, the smell of an epiphyte after blooming. It’s more than fifty years and she’s reading the same hardcover book. Twenty years from now I fear I’ll still be trying to describe her. Is she flat like drizzle falling on the beach is flat or is there depth to her like the beach has depth? Is it raining? She hasn’t ears, they’re hidden by pasted down hair (from the rain?) For weeks a castoff sofa has lain on Industrial Drive’s blind corner by the sheet metal works. I saw a couple standing behind it, embracing. I’m sure the woman was weeping even though I couldn’t see her face. There were tremors of reconciliation like the convulsions of a sobbing child finally done crying, gasping for air. With Girl on the Beach, I’m looking straight at her and can’t tell if she’s white, black, dead, alive. It’s the oval face of a mannequin, of a harlequin, the face of the American brushing her teeth in the horror film when her cheeks flake off in her hands. She has her own weather. Smudge of burnt ochre is her neck. She hasn’t a mouth. Not one gull flaps through her space. I can’t discern what she’s wearing—striped skirt or is it a towel across her legs? Or is a towel draped about her arms? Covering her chest could be a white blouse beneath a grayish top. Her left leg, bent, a mass of pigment looking like a drumstick torn from the slaughtered bird. Her right leg: shapely, supple, finely contoured. But nothing else has definition. There’s a beach chair but she’s sitting on the sand, maybe on a blanket or a sheet, one sandal visible beyond her feet, crooked elbow of right arm resting on the chair. Her centrality is off. Her eyes lack pupils. Light without sun. Sun without heat. She’s neither inside nor out. Though here she is, coming at you, sitting there reading, Girl on the Beach. Howard Faerstein Howard Faerstein’s full-length book of poetry, Dreaming of the Rain in Brooklyn, was published in 2013 by Press 53. A second book, Googootz and Other Poems is forthcoming from Press 53. His work can be found in numerous journals including Great River Review, Nimrod, CutThroat, Off the Coast, Rattle, upstreet, Mudfish and on-line in Gris-Gris, and Connotation. He is Associate Poetry Editor of CutThroat,A Journal of the Arts, and lives in Florence, Massachusetts. The Garden (a story puzzle)

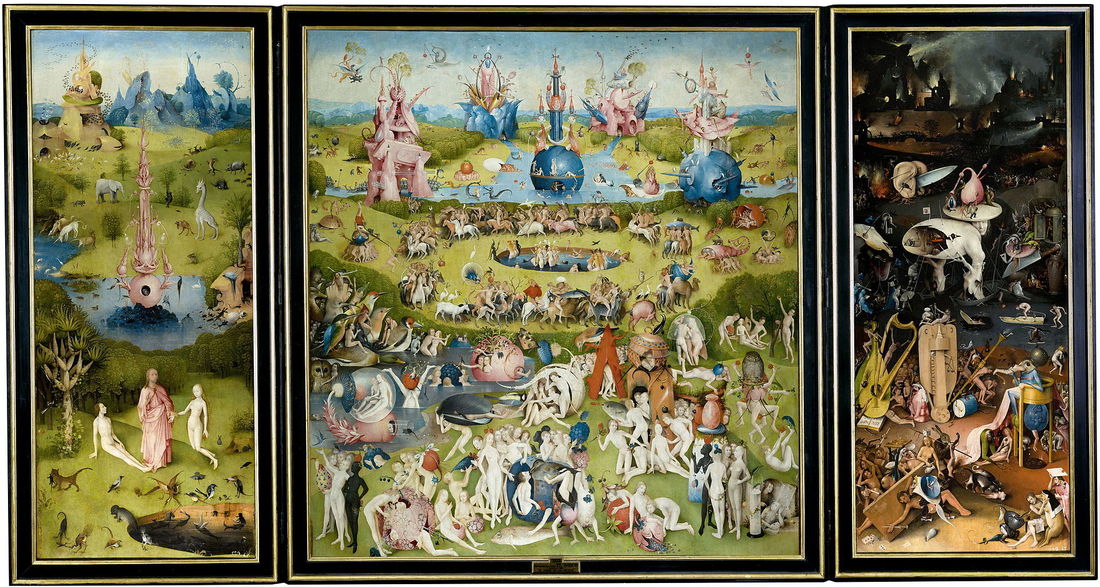

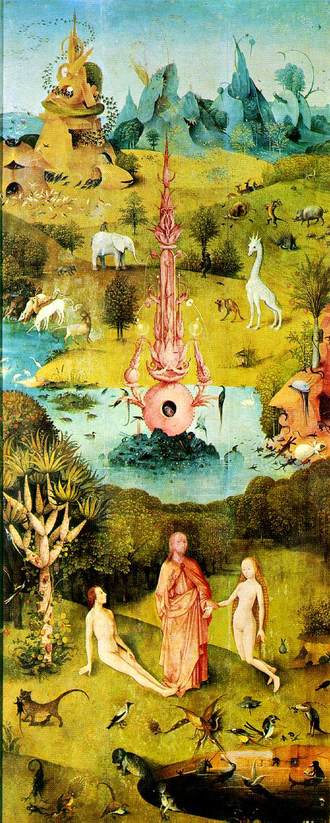

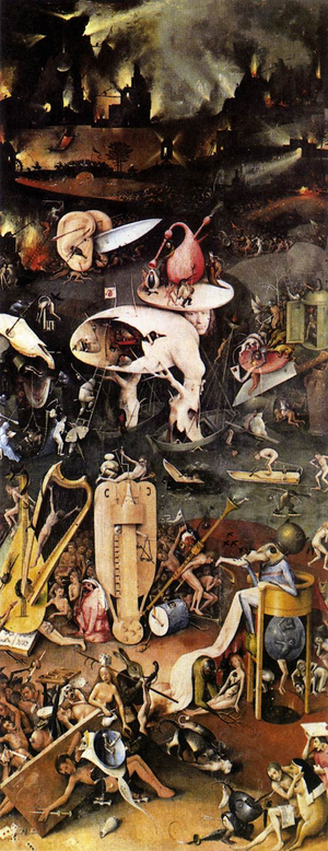

Who am I in “The Garden of Earthly Delights” by Hieronymus Bosch? Nine…eight…seven…six ringing in the darkness. I have to get away, there’s danger back there, they’re going to cut my heart out. I flap my wings smoothly, silently in the night sky, turn, then glide as if gravity didn’t exist and hope they can’t follow me. I coast over a burning city, buildings silhouetted by flames. I bank and dive, see a red sail on a lake and a multitude of humanity, like lice, swarming out of it. Farther away I see ghostly figures lining up at a glowing gate as if there’s some escape, and that’s just the beginning—a tiny part of this vast senseless landscape—so beautiful it must be hell. As I fly lower, soot starts to burn my nostrils and a cacophony of horns, crackling fire, and cries of agony fill my head. I fly over a razor-sharp knife slicing apart two monumental ears, which almost stops my heart. I can almost feel it, that knife cutting me—a long slice under my breast feathers—sudden pain, a feeling of life hanging in the balance, of illusion upon illusion, of moments frozen in oil and pigment. I fly as fast as I can, past a house made of bone held up by bone tree-trunks, a platypus monk, until I reach The-Land-of-Tortured-Musicians. There’s a guy strung up on a harp, one tied to a lute, and one squashed under it with a musical score painted on his bare ass. Some guy’s pointing at it, seems to think it’s hilarious. What did they do to deserve this? Off-key recitals? Derivative compositions? Nearby I see a lizard wielding a sword which has a heart impaled on it and there’s a man with a hypodermic needle stabbed right through his hand. Out of nowhere comes the drone of a buzz-saw getting louder and louder. I have to get out of here before it cuts me open. This place is boxed in by wooden columns which, for some reason, I can’t see around. I fly at a column, sink my talons in, flap my wings to get balanced, work my way around and look over it. What I see is an abyss, a plane of non-existence. But I know there are other worlds. I’m the symbol of divine wisdom after all. The buzz saw’s closing in. I leap, find myself where nothing exists, not even me, then bam, a wooden column comes flying at me. I sink my talons in and swing around it into The-Land-of-Naked-People. They’re all dancing, swimming, sticking flowers up each other’s asses, and making out in glass globes and giant muscle shells. I alight on the first perch I see, which is atop of a pink scalloped stand with human arms and legs frozen in dance. This place is filled with birdsongs, laughter, and the perfume of flowers and fruit, all the sensual delights. I fluff up my down and settle in. Then I realize I’m a bit peckish. I swivel my head 180° to the right and see a number of giant berries here and there. The trouble is I’m a carnivore, a predator of the night, and the only small prey I spot is a rat in a glass tube. Then I swivel my head 180° to the left. There I see six naked people picking apples from a tree. One of them is carrying giant strawberry. “I’m starving!” the strawberry man cries. “Let’s have a banquet,” one of the women says. I call out “hoo, hoo, hoo, hoo-hoo,” hoping they’ll invite me. But just then a faint voice starts echoing in my head saying, “scissors, clamp.” “Let’s have roast fowl!” one of the men shouts, then “scalpel!” Someone hands him a huge knife and he comes running at me. I take off just as he lops off a few of my wing feathers and fly across this land of many creatures, two lakes, a pond, and constructions made of rose quartz and blue marble. People here seem to do whatever amuses them no matter how senseless, like crowding into a red teepee-tree and doing weird things with giant berries. Soon I reach another wooden column, sink my talons in and shoot across the plane of non-existence, then grab onto a new column and swing into a much calmer place where there’s hardly a sound. At the centre of this land God is introducing Eve to Adam, which would explain why there are no other people here. This place has blue and pink constructions too, as well as a pond and a lake. I alight on the edge of a round hole in the rose quartz central fountain. It seems to be made just for me, so I fluff up my down and get cozy. The place is conspicuously lacking oversized berries, but it does have a lot of small prey—bunnies, lizards, and a bunch of little buggers I can’t identify. I’d go out and kill something but I’ve totally lost my appetite. This has to be the dullest land in the world’s I’ve visited. There’s nothing to do but stare at a ocelot tormenting a newt. It’s unbearably quiet too, just the sound of the water trickling from the fountain. I can hear my heart pounding in my ears getting louder and louder. It seems important to listen to it. Suddenly—I suck in a breath—it just stops! All that’s left is a dull ache under my breast feathers. I don’t know what to do so I just nest here and wait for something to happen. It seems like an eternity. God keeps introducing Eve to Adam. The ocelot continues to torment the newt. It never gets dark. Finally, I can’t take it anymore. I fly out of my hole and back to the wooden column I crossed over before. I dig my talons in, traverse the plane of non-existence, then I’m back in The-Land-of-Naked-People with all its laughter, chatter, and birdsong and realize this is the only place anyone can possibly exist. It’s so crowded it’s hard to find a bare spot so I alight in a shallow pond and sink into its warm water next to a familiar looking boy. He’s frowning at me with worry, so I say, “hoo, hoo, hoo-hoo, hoo,” and give him a gentle peck on the cheek. He lights up with joy and puts his arms around me which feels so good my heart starts beating again, then-- My eyes open in a glaring white place full of beeps and drones. Things are foggy. I have a strong urge to pull out a tube that’s lodged down my throat. I try, but my hands are tied down. Then… Oh! Everything comes into focus—the recovery room. I’m a forty-eight-year-old medieval-art-historian heart-transplant-recipient. I notice my wife and son standing there. He has his hand over his mouth and she’s crying, but she’s crying for joy. Sheila Martin Sheila Martin: "My first novel, The Coney Island Book of the Dead, An Illustrated Novel, recently won the 2017 McLaughlin-Esstman-Stearns First Novel Prize. In addition I have pieces in the current issues of four literary journals: Ginosko (#19), Earthen Lamp Journal (Volume II, issue 1), The Legendary (#69) and Volume 1, Brooklyn. I also have an unpublished novel that takes place in an art school for which I am seeking a literary agent." |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|