|

Flayed What looks like something alive without skin becomes meat for the fry pan, the meal for today. The only knife they haven’t found is a good size for the carcass, this one a spring hare. Not fat enough. First the pectorals, flapped open like my Oskar’s vest the night they marched him into the forest. Sternum cracked, yanked out, ribs attached, lifted into the cast iron pot, laid on a bed of early greens and sorrel for a sour stock tomorrow. Legs severed at the hip joint, slid into the last of the milk to soak. What’s left is a narrow boat of flesh where heart and stomach and sweetmeats cool. Boiled, they’ll give strength, but entrails and lungs make a soup bitter. They could go to the hound if he hadn’t run off or been butchered for food, so into the bucket, chum for bait-fish. They can’t stop the river or the perch in its weeds. Braised in a bit of lard, milk-sweetened haunches and breast meat, forelegs with their thread of marrow. As for the spine, we’ll suck meat from its bones. Sundown, tuck the children in. Bury the pot in the food hole, scatter the feet. Dim the lamp, hide the oil. They took the chickens, eggs, the cow, the pretty girls, the men. By day, the Germans. By night, the Partisans. J. C. Todd J. C. Todd’s books are FUBAR, an artist book collaboration (Lucia Press), What Space This Body (Wind Publications), and two chapbooks. Poems have appeared in the American Poetry Review, Paris Review, Virginia Quarterly Review and most recently in the Beloit Poetry Journal, Thrush, and Valparaiso Review. Winner of the Rita Dove Poetry Prize, she has received fellowships and awards from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, the New Jersey Arts Council, Virginia Center for the Creative Arts and the Pew, UCross, Ragdale and Leeway foundations.

0 Comments

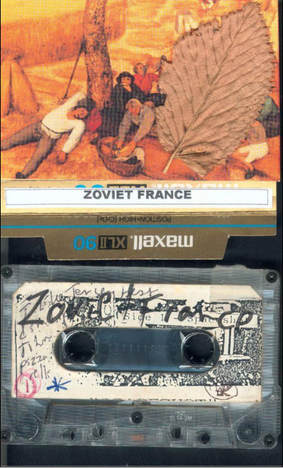

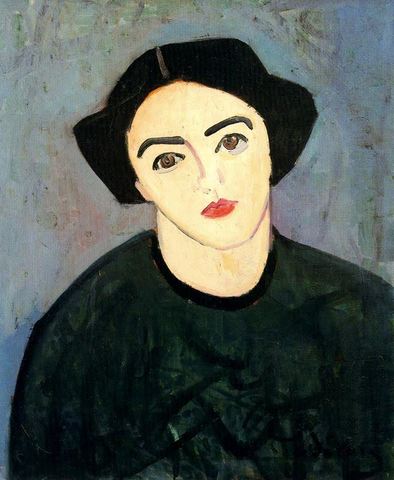

The Artist

She jumped out the patrol car’s backseat, indifferent to being let go with just a warning and angry that they kept the spray-paint cans when they picked her up on the other side of town. They’ll probably use them to paint their kid’s bikes or wagons, or some stupid table in their garage. The air smelled like rain, so she hurried to the closest bus stop and rode until reaching an area where it looked like the cops would have more serious crimes than graffiti to worry about. She laughed when she jumped off, stepping down almost straight into a hardware store. The itch surfaced as soon as she reached the aisle that mattered. Her fingers trailed along the cans, tapping the caps when she came to a favourite colour. She couldn’t help it. It’s not like there were regular art supplies at the foster home she’d been dumped in this month. Or any of the other foster homes in any of the other months for that matter. Mr. and Mrs. Foster were just as interchangeable to her as she was to them. “Can I help you miss?” an elderly, aproned employee asked. The way his shaggy white eyebrows arched made her feel guilty. Not like she was going to try and lift something – more like, why wasn’t she at school this time of the morning? She was almost eighteen, but not quite; the last thing she needed was this old geezer calling the boys in blue. “No thanks. I was just looking for a clear coat,” she said with a toss of her hair that made her look like every other idiot teenager. “It’s for an art project I’m finishing today at school.” He walked away and picked up a broom that leaned against the wall. She watched him sweep for a moment then walked down the next aisle. Rifling through her pockets, she came up with a dollar in quarters and three nickels. Not enough for even one can. She wasn’t a thief, no way. She walked toward the entrance. When she reached the part of the floor that tripped the automatic sliding door, a large yellow cardboard sign advertised stacks of blue electrical tape - two for a dollar. She picked one up and rolled it around in her hand, then picked up another and made her way to the cash register. The man stopped sweeping and came over to check her out. She smiled at him sweetly and like she often did with strangers, wondered if he could be her grandfather. She wandered a few blocks in one direction, then another, looking for an inconspicuous target. The main avenue ran north and south, so she turned right at a light and headed east. A few antique stores and galleries dotted the street, but you could see auto repair and construction supply businesses encroaching into what probably had been an arts district not too long ago. The abandoned building cried out to be something more, with its rounded corners and glass block windows. She looked around to make sure no one from the neighbouring businesses had a reason to come her way. Confident, she walked around the entire back wall and placed her palms against different spots as if she were feeling for a heartbeat. She worked randomly, furiously ripping the blue tape into short and long pieces. The work evolved minute by minute. She reached up and then quickly crouched to the ground, leaving one thought unfinished and moving to the other end to start something completely unrelated. Her fingers hurt from rubbing the strips down into their shapes hard enough to make them stick. Shadows began to cast over the building from the low hanging clouds, which suddenly appeared. Her stomach growled. She stood up and stepped back, wiping away a tear and wishing she still had her cell phone so she could take a picture. With no money left, a bus ride back was out of the question. She started walking back toward the main road to thumb a ride. The Fosters would be angry when they got another message from the high school that she hadn’t been in classes. Five months. She’d be eighteen in five months. Out of the system and free to go wherever she wanted. She’d heard graffiti was considered an art form in New York City - maybe she’d go there and teach them what you could do with blue electrical tape. Vicki Roberts Vicki Roberts is a writer and graphic artist who lives on Florida's east coast. Her first novel, Oldsters, was published in 2017. In between writing short stories, which have been published in various magazines and anthologies, she is at work on her next book, The Year of Gwendolyn Presley Flowers. Her life selfishly revolves around literature, music and art. Catch up with Vicki at https://iamvickiroberts.com The Birthday of the Infanta 1 As a girl, I went an entire day once without eating to walk with the Duke in the Queen’s perfect, geometric rose garden, my waist no larger than the clasp of his hands. When we walked in the garden, the Duke kissed me, a brush of his whiskers near my face drawing me into his world of tobacco and male scent. This man who would give me fifteen children and become my comrade for decades, was older than my oldest brother Diego, but I did not mind. He was polite, and I knew marriage to be my duty; besides, I thought in my child’s mind, he will die and then I will have my children to play with and a palace to dance in, where I will strew rose petals of every colour in the rainbow. It is alive in me today, this time so long ago in the past. Is it because I am dying? I watch my breath travel in and out of my ancient lungs and know that soon all this will end. The wise men say that when we die, we return to the place of our birth, though the priest told me I will travel to heaven or hell, according to the life I have led. And what of that life, which will be my fate? As a child, I thought nothing of death, only the future that lay before me like some great green meadow, the sun on my young skin, with no thought of what comes after. You may marry a man or the Lord Jesus, my dears, the Holy Mother told us. She was a good woman, kind in her black robes and paper-white skin. At night when the convent was silent and only lit by the moon, a girl named Maria showed me her playing cards and laid them around us in a circle. She giggled so in the moonlight, yellow curls on her cheeks. My God, how beautiful she was! An angel does not describe her fairness. We each chose a different card, mine snarled with a snake and a shining star, hers with the Lord Jesus. So that was our destiny—I would take the path of the world and the serpent, she of God. We brought our lips together to seal our fortunes and swore to be friends forever. I held her face in my hands and looked deeply into her eyes. “You are my sister,” I said. “I will love you as no other. I swear to this.” We pricked our fingers and tasted each other’s blood, though by the time I walked with the Duke in the garden, I had forgotten her. For a girl of my station, the preparation for marriage took months. I prayed often as the nuns instructed me in my duties—to my children, my husband, God. After my walk with the Duke in the Queen’s garden, there were more prayers and recitations. I was so famished that day, forced to wait until the sun sank below the mountains and my servant unwrapped my engagement dress from my body. How good to be unsealed from that coffin of lace and feel a breeze against my naked skin. I took a sip of chocolate, my first food of the day, one chicken wing, a basket of cherries. My mother said I was too fat and needed always to allow the Duke to encircle my waist with his hands. Other girls were more slender, their breasts small. Once when we played at the ocean, I saw Maria’s breasts silhouetted against the sky, and her beauty left me breathless. I could have been taken for a boy, were it not for my head of brown curls and small lips. Still, in the garden, the Duke said I was a bird, a starling or a humming bird. “I am marrying air,” he said. For the hundredth time that day, I wondered if I would be frightened when he came to me, or if, like a sea captain, I would ride the waves of my destiny into very old age, when Maria and I would meet again, never breaking our promise of love. I saw my future husband one last time before our vows, on the day of the Infanta’s birthday, when gifts from all the royal courts of Europe were opened and my brother’s painting of the Infanta unveiled. I wore the same dress that day, black lace cinching me tightly at the waist, ruby jewels around my neck, and when the Duke gazed at me, I felt excitement for this new world I would inhabit, led by the serpent and the flesh. But now, when I remember that day, I think mostly of my brother’s painting of the Infanta: the tiny child in her white satin dress standing out hard and straight from her body, dogs and dwarfs playing at her feet; the King and Queen at the door, anxiously peering inside. Diego’s canvas was huge, rising all the way to the ceiling, and he had put all of them in it, including himself. “Why not?” he told me. “They were here each day when I painted the picture—the musicians, the dwarfs, the King and Queen, Las Meninas, the ladies-in-waiting. It was a carnival. Why should art end simply because of a picture frame?” 2 “Quieres que tu chocolate, ahora senora?” A girl stands before me with a pitcher of steaming chocolate and I nod. I have come to the palace one last time, to sit in my place before my brother’s painting and ponder its meaning. So much has changed since he painted it. Philip is dead, I am in my eighth decade, and Spain is no longer the centre of the universe. Once Philip’s empire stretched three billion hectares to every corner of the earth, but no longer. The English have supplanted us, though the fame of my brother’s painting only grows. Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velázquez, knighted to the court of Spain for his service to the King. Painters as far away as Italia and Inglaterre come to view it, to study his greatness and learn from his work. Diego was ambitious. To qualify him for knighthood, a tribunal of the Inquisition had first to investigate our lineage, to show no Moorish or Jewish taint. The ordeal took seven years—the auto-da-fé waiting—that yearly spectacle where heretics are burned alive to cleanse the faith. Today people gather in greater and greater multitudes to witness the pitiable sinners. It is Spain’s holiday, to which knights and representatives of neighbouring cities are invited, the windows of the houses closest to the burning reserved for the most wealthy. The autos last from seven in the morning till deep into the night. I went only once, where I saw two sodomite lovers burned alive. Those gallant souls could not touch, but they looked into each other’s eyes and remembered the time they had shared, knowing that love like that is always worth death. Later the Tribunal flayed a child alive for refusing to bear witness against its parent. Our family was proven spotless, thank God. Philip was glad. He told my brother that he once saw a Medici cardinal torture a mouse on a tiny rack for stealing cheese, and after that he wanted none of it. He would be the Planet King: his dominion stretched to every corner of the earth, and besides, he was the fourth Philip just as the sun was the fourth heavenly body to encircle the earth. He surrounded himself with artists and dwarfs, filled his castle with dancing bears and giants imported from Russia. Every spring theatricals were held, and my brother was given a private residence in his court. Philip admitted all to celebrate the birth of the Infanta Margaret Teresa, from scrubwomen to lepers, and now she was five. On the day of her birthday and of the painting’s unveiling, all were in attendance: the dwarfs, the lepers, the ladies-in-waiting, even a family of gypsies that lived outside the castle and had been invited to read the Infanta’s birthday fortune. The woman predicted only rosy children and gold-tinted clouds for the child. How could she do otherwise? A servant pulled a cord and a curtain slid to reveal the canvas. Philip stood before it for several seconds, then asked Diego for a small brush dipped in red so that he might make a final flourish, painting his family’s coat of arms on the chest of Diego’s self-portrait, knighting him in the painting as he would soon do in real life. Slowly a smile spread on Diego’s face, and he laughed. He grabbed Doña Isabel, one of the Meninas, the ladies-in-waiting, bent her backwards, and kissed her. It was clear they knew each other well. For the remainder of the afternoon, she sat on his lap as he and Philip drank wine and ate from a celebration table heavy with all manner of food and libation. Four years later, my brother died of a fever. He accomplished so much in his lifetime: over one hundred canvasses of royalty and humanity and this masterpiece of the King’s child that stares at me each day daring me to decipher its meaning: why does Diego show us this world inside his canvas that is like the real world and at the same time not? It is a hall of mirrors. He has put himself in the centre of it, brush in hand, peering at me from behind the back of a huge canvas as his subjects do as well: the Infanta, the Dwarf, Las Meninas, the dogs. A nun and others cluster about. There is no separation between art and life, Diego once told me. Is that its meaning? Behind all of them, reflected in the glass that Diego put at the rear of this invented world, are the Infanta’s mother and father, King Philip IV and Queen Isabella of Spain. How Philip loved his daughter. Though the gypsy gave her endless decades, she only lived to twenty-one, the Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, before dying from the birth of her sixth child. Her husband who adored her was beside himself with grief. And I have outlived them all. 3 I will leave this body soon, this shelter that cloaks my soul. At night I do not sleep. The girl has moved my bed next to the window, so that I can gaze at the moonrise and watch the transit of the stars. A year after my marriage, I saw the young novices walk toward their vows, their pale bodies dressed in white, faces lifted to God. The girls chanted as they walked, looking into their future, toward all I would never know. I was not jealous, for was not my path equal to Maria’s, and does not all life lead to God? But now I am not so sure, and I wonder if Maria’s life was not the luckier, spent in her devotion. The Duke was a respectful husband and we enjoyed each other. I will speak of it frankly. The seas we rode together were warm. He gave me so many children that on my celebration day, I am surrounded by generations—the smell of leather boots and young boys’ tousled hair; the frothy petticoats of girls. But what is that next to the mystery of the universe? There is a natural philosopher in Italia, I have heard, who has looked at the heavens through a special device that tells him the earth is not the centre of all there is, that instead we are no better than any object in the sky whirling in the blackness, and if that is so, only God can explain our meaning. The Tribunal does not burn him, but they have imprisoned him and destroyed his work, and still he will not recant. Diego told me once that he painted the picture as he did, because his purpose was to capture the truth of the girl in the studio, the dogs, the dwarves, Las Meninas, rather than concoct a deception. What we see is sacred, he said, because it is true and where truth is, God is. Truth, he said, is a reflection of the divine. Judith Dancoff Judith Dancoff’s fiction and essays have appeared in Creative Nonfiction, Tiferet Journal, Alaska Quarterly, Other Voices, and Southern Humanities Review. Her stories in Tiferet and SHR were both awarded best story of the year, and she has received residencies from Hedgebrook, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and an upcoming residency at the Djerrasi Resident Artists Program, June 2018. She holds an MFA in writing from Warren Wilson College, and an MFA in filmmaking from UCLA. Shouting at the Ground, Through the Trees “A silent man, walking in solitude by a mountain stream… We begin to see what is real and what really deserves our allegiance.” Gary Snyder ☉ Listen to the radio show as you read this: Wreck Zoviet France Shout 1190 Roquette, Pimprenelle, Hirondelle, Lézard des murailles, Muquet de Mai, Bruyère, Patience, Fongère, Sapin, Chataigner, Laurier Franc, Pissenlit, pie-grièche à tête rousse, Guêpier d’Europe, Mauve des Bois, Chauve-souris, Épicéa, Fauvette, Traquet motteux, Marronier d’Inde: repeating any of these French flora or fauna species in any number, in any order overandover will transport you to the place I am about to describe because as we all know, language is the basis of our world, how we perceive it, how we construct it, how we negotiate through it, and, through mantras, transcend walls, borders, and this “blooming buzzing confusion,” as William James described our world. Religious people, monks, gurus, musicians, and poets all know this. Language is the effluvia that allows us to interact, to inspire. And the above is my mantra, my escape clause ... The reason may very well be that this particular album has a long personal history: It has stood by me, has enchanted and provoked me over the years but most eidetically for a long period of self-imposed hermitude in the south of France – and elsewhere. It justifies and endorses the very solitary life that is both sought and endured. I recorded Shouting at the Ground in pre-digital times from vinyl to cassette in the basement studios of WFMU shortly before I moved to France. The magnetic cassette tape I chose was already occupied by other sounds, and yet, I had no moral qualms about recording over it. This was a tactic generally frowned upon by audiophiles and WFMU DJs obsessed with high fidelity. While some people pack a rucksack with an emergency medical kit, a hip flask filled with a liquid of some proof, or a big lunch, I packed mine with cassettes and an apple. I knew my survival would hinge on essential sounds the way others would never forget a canteen or a pocket knife before they set out on a hike. I spent great, long stretches of hermetic time out of Paris, in the South of France, in a stone house on a hill to the east of Albi and just north of Castres and Mazamet – a beautiful area with a view of the Montagnes Noires; there are few tourists, few locals, and a broad selection of great, modest, underrated Languedoc wines and wonderful breads such as the miche, which I describe as made of water, salt and flour in the shape of a baseball catcher’s mitt. Albert, the property’s caretaker, picked me up at the train station in June. His English was limited to a dozen words. My French was a timid stream of nouns and unconjugated verbs. But somehow communication happened: He showed me where everything was: silverware, work gloves, linens, wood for the stove, some basic provisions: bread, cheese, coffee, eggs, wine. How to open the mint-green shutters and windows. There’s no TV, just an old portable radio with a cassette deck. That’ll be my companion for the next 10 to 12 weeks. I am going to write a novel or maybe just fill the endless time barely passing with something that pretended to such a purpose. But also, I just wanted to BE – be away, be somewhere else, be myself in relation to the world and all its attractive and distractive features ... and, I was there to make money as a kind of tree trimmer/lumberjack – and upon further research, discovered I could have been called a land manager too. X’s uncle drove up from Toulouse to make sure I full comprehended the importance of my task. He was a dapper man with a moustache you associate with movies from the 1940s and an aptitude for English he was proud to show off. My days were simple: It was summer, I did not need an alarm; the sun managed daily to part the mist and squeeze through the slatted shutters at just past 5 AM. I would rise, and as I reheated yesterday’s coffee, I might scurry out briefly to touch dew on grass, behold it, and then return to write until 7:30 with equal cups of reheated coffee and cold Ricoré [instant chicory coffee substitute], which was perfect for dunking hunks of my miche brought fresh ever 3 days by Albert on his way to work. [Are the crazy people those who do this kind of thing or are they the ones who never-ever experience this dunking delight in their entire lives?] I made a big breakfast, packed an even bigger lunch, dressed in my holey work pants, high rubber boots, checkered shirt and bandana, checked to make sure I had my citronella oil insect repellent before hiking off to my job along the rusty barbed wire that kept a few grazing sheep [moutons, I repeat overandover] in their part of the pasture, la-la-ing, singing, repeating hypnotic phrases in French – “le tapage des oiseaux ivres de lumière” [The twittering of birds drunk with the sun, Charles Baudelaire] – blowing kisses to the sky, humming, talking to a rabbit or a pheasant – the only thing a spider web has caught this morning is dew – along this magical petit chemin, a path consisting of 2 old tractor ruts that attract many audio and olfactory delights – like how a story line through a novel attracts logic and intrigue. I notice that the telephone poles wear tin caps to prevent them from rotting. Oblivious to how ridiculous this would all seem if viewed on a hidden camera. The permanence of elements – stone walls, like slate, like a stump wearing a green sock of moss, like this old rusty saw attached to an ancient pole, shiny with a hundred years of a hand gripping it – contrast with the floral effluvia or the tufts of early morning mist caught in the grasses, illuminated from a mysterious source as a breeze runs its fingers through the tops of the trees. The brouillard [it’s onomatopoeic, it describes mist in sound] envelopes you in its swaddling layers as it descends into the shad of the valley, leaving behind the stone house. The work [over a summer and then through a good deal of the following winter] was in a beautiful woodland, a tree farm of lumber-bound firs and pines, but to me just a wood of somewhat hypnotically, symmetrically planted evergreens – perhaps 10,000 of them in total. Upon arriving in the wood at 8 AM, I lap on citronelle to neck, head, hair, and arms to keep the gnats away. [This mostly works only if I believe it does]. I put on my work gloves and begin trimming branches up to a height of 6 metres, using 2 tree pruner saws mounted one on the end of a 2-metre wooden pole and the other on a 4-metre pole. I take periodic breaks for a sip of iced water, juice, an apple, some nuts or I might write something down, an observation, a line to a poem never finished, gibberish. “How does one see the thing better when others are absent? Is looking like sucking: the more lookers, the less there is to see?” -Walker Percy As I worked I heard the crackling of branches, my groans and heavy breathing echo through this wooded parcel; my body already steaming from the exertion and its not even 9:30 AM. The saw dust falls from the scythe-shaped saw and sticks to my skin. I am totally alone here. At the end of my workday – 2 PM [before the full heat and full annoyance of gnats] – sawdust covering my head, pine resin drops sticking to the hairs on my arms, I noted how many trees I had trimmed. If I trim 80 trees at 5 francs per tree, I could earn an OK living wage of about $66 a day in the middle of nowhere. From my scratchy notes it looks like I averaged about 95 trees in 5 to 6 hours, or about 1 tree every 3 minutes. I see from my rows of figures in a notepad that on good days I’d finish 149, 145, 131. The harder I worked in the morning, the less hours I’d have to put in and the more time I’d have for living and writing. The pace is sometimes frustrated by resin that builds up on the saw blade. This I have to clean off using rough stones and a cloth soaked in rubbing alcohol. [Back at the house I might use a rag soaked in gasoline]. Then I walked back home – the 40 varieties of flowers along the way mock any hubris we may manufacture – with a plucked bouquet of wild flowers or a pocket full of wild strawberries. I stop to listen to the bees buzzing, the birds chirping [I only look them up many, many years later: Skylark, Common Linnet, Crested Lark, Swift, White Wagtail, Serin, Corn Bunting, Goldfinch and Fan-tailed Warbler]. The running brook: I want to record it and, like Beethoven getting down on his belly to listen to its gurgle, I try to learn its enchanting secrets. The mud sucks up my boot; the mud smells a million years old. Two young lovers holding hands in the distant midday sun, heading to the reservoir to go skinny dipping. I have seen the gleeful and carefree on my days off, lying, white-skinned, on striped towels along the shore. A teenage summer doing nothing is a summer well-spent. One day – maybe it is how like a good frame enhances a painting – the stillness frames the ambient sounds. I hear the cows [vaches] 100 meters off in the pasture slowly chewing, each at peace with her own halo of flies. I find two mouton skulls, parched and bleached; I bring one back to place on my work desk. I run a steamy tub of aromatic water which was – I don’t remember – probably some mix including sage, chamomile, or orange peel, offered as a going-away gift by X whose resentment at my leaving reminds me of the girl in the movie Betty Blue. I kept this observation to myself. [I refuse to even entertain the notion that she is secretly relieved that I am gone]. Probably more than once you could have caught me drinking some of this bathtub tea. I press the PLAY button and Shouting at the Ground begins to waft, to loop through the house as I lay in the bath. I am aware of my body and its constituent parts, by how much each muscle and joint aches. My body has been rearranged by honest work in the thorns and hard brittle twigs crackling to produce a glorious sensation of pain, callouses, blisters, cuts, and scratches – I am in good shape but I hurt. Shouting is looping as I eat a lunch of local cheese, hunks of miche, a salad of greens grown out back, or omelette, artichaux, avocado salade, cup of coffee, while fiddling with the radio dial to listen to human voices discuss issues on Radio France. I return to Shouting; it loops and drones as I climb back up the stairs, as I take my chair, as I begin to write, sitting in the blazing sun at a desk with a view of the Montagnes Noires in the distance. The ritual-routine is: Wake, work, bathe, eat, listen, write. Invariably, and perhaps a thousand times during my 10 weeks of hermetic non-contact with other humans, I would press this tape into its carriage, press PLAY and set it to auto-reverse on this old padded-casing cassette deck and AM-FM-Shortwave radio [bent antenna] and just stare. I was indeed creating auto-reverse loops of loops, reimagining the orbits of the universe and the orbits of our preoccupations simultaneously. Most of Zoviet France’s compositions hinge on pre-digital looping techniques [which gives them a palpable organic-mechanical feel]. Loops are closed circuits, are rings, are halos, are lifesavers that continue on into eternity unless you switch them off at bedtime or a lightning storm causes an outage. Music is based on repeated patterns, rhythms as prescribed sets of notes repeated, rhythmic repetitions. Music and the things music makes us do like dance, dream, enjoy the moment, are hot-wired into the deepest of natural processes. Nature is a series of circuits, the seasons, perennials, precipitation, making the audio loop an analogous ecosystem of sorts. And these loops are Zoviet France’s way of making a certain sense of all these cycles.

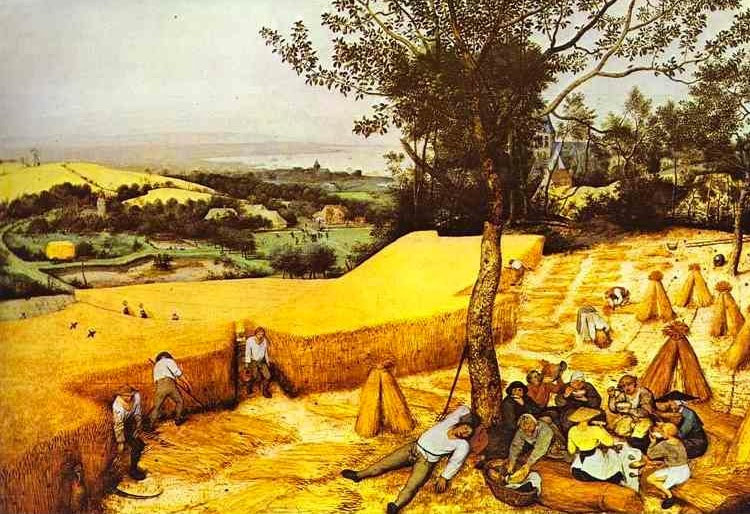

The early tracks send me [I hope you too] off on a surreal, lightheaded walkabout with unsure footing down a long, dimly lit path serenaded by exotic instrumentation and flautists as anonymous as the wind. “Smocking Erde” has its lurking and heavy-sighing-among-trees vibe; “Palace Of Ignitions” with its mesmerizingly open plucked strings that act like a geo-psychological reconnaissance device, while “Come To The Edge” represents a pure, organic loop that places you in the realm of maybe a lesser-known Monet, lost in the mesmerizing sweep of the outdoors and various fleeting, disconnected snatches of mysterious audio blossoms. Albert, a solitary man with cheeks urged red by the sun and wind, and a stoop that forebodes our lot as we head toward dust and worm, delivers a huge miche, a bottle of vin rouge that he holds up over his head in his earthen hand, a basket of potatoes and tomatoes from his own garden. He tells me this house was burned down during WW2 by the enemy, having served as a strategic outpost for the Resistance – it’s all about the view in both war and peace. I tell him the howling wind, the clattering of a loose shutter, and thunder kept me awake last night. I don’t tell him I kept dreaming about cars full of hoodlums pulling up outside because I couldn’t figure out how to phrase it in French. He brings me to the west side of the house; he shows me the shale shingle wall that protects against lightning strikes. Chauves souris [bats] live under the shingles – Je les ai vus – he smiles as he shows me. [I first translated “chauves souris” as “hot smile” but that, of course, was wrong]. They come out at dusk. Je sais. Hundreds. Je sais. Bats are mostly our friends because they eat mosquitoes and gnats. Some eat more than a thousand insects per hour! And with that fact and a flip of his beret, he departs. I doze off, awaken in the sun out back and, in a squint, I see a green lizard nuzzled in my solar plexus. I laugh and the laughter seems to be coming from a foreign body – not me. I notice the dark splotches of mosquitoes smashed against the white wall; they remind me of the eyes of some women in Paris cafés late at night. Some tracks on Shouting escort us into a world out of tune, a world devastated by industrial forces and their exuberant magnates... While the atmospheric pipes and flutes on “Dybbuk” help realign us with our surroundings. I might be in a hypnagogic state now, somewhere between reverie, exhaustion, a pastis [yes, why not], and the lightheaded effects you feel just before an electrical storm. Shouting has a bit of an idyll-invaded-by-industry dialectic, of jarring misalignments and dissonance [“Stoke Blauwers,” “Fickle Whistle,” “Carole The Breedbate”] in a world upside down, which then, just as suddenly, shifts and sways to audio antidotes [“Marrch Dynamic”] to disharmony and then pretty much grounds you up and casts you to the ethereal winds [“Wind Thief”]. My self-imposed solitude meant I saw other humans only once or twice a week briefly: Albert and then my weekly trip in the old white Peugeot 505 station wagon to greet the smirky, bright-eyed cashier whose check-out line I would always choose in the local supermarket. I would cherish that lovely smile for the following week. Or there were the wine givers, adjacent to the boulangerie, a couple who seemed to inhabit a dark cave or had once modeled for a Millet painting. They magically tapped vin rouge ordinaire from a wall spigot into heavy liter bottles with saved corks. They insist you take a glass from a ledge and toast the fetid basement air and I will compliment her and I will thank her. I did not bring music with me on my promenades [no Walkman] but “Shamany Enfluence,” serving as Shouting’s sprawling, epic looping, immersive and Buddhist monk-like, ethno-ambient chanting and moaning centerpiece gives you the sensation that you are indeed sweeping across the primordial topography on a sort of magic cloud. It served me well as remembered soundtrack, enhancing my interactions with, and my wanderings into, these strange surroundings, these deep gazing people who have had their feet on and in the earth around here for a very long time. The organic loops are drawn like buckets of water, right from the earth and, yes, I daily drink deep well water, cold even in July – the music, the water. When it rains I work or maybe I don’t. My raincoat is fit for a cinematic phantom that one day spooks a lost dog. I drink the rain water that flows down my face as I pick murs [raspberries] and watch an old lady hobble by – where does she come from; where does she go? – bent in half, no more than 3 feet high, with her knobby walking stick and laced-up boots to support her ankles. The final track [“The Death of Trees”] offers you an audio corollary to some spectral viewpoint – you simultaneously feel depth as if indeed the sound is outlining some hidden cul de sac. Call it enchantment or meditation or a smelting of self, of dreams, of location and sound so that the mind is released from all grief and distraction. Many of the album’s tracks are perhaps about negotiating a landscape, attempts at engaging our earth, which is hindered by the collateral damage we know as “progress.” It’s not as if Zoviet France’s analogue, pre-computer collaging is program music but they do seem to be tinkering with a visceral narrative, a poetic dialectic between nature and man, which, although Zoviet France was thoroughly groundbreaking, was also a central fixation of Romantic-era musicians and artists: how humans with their emerging self-awareness fit into the grander scheme of nature. We think: Beethoven, Berlioz, Grieg and Mahler; Strauss claiming that music can describe anything, even a teaspoon. But there are also many Zoviet France contemporaries I will not now name. I will instead pick up the young toad and carry it out of harm’s way, placing it on the shoulder of the path, shoving it along into the brush. All of these efforts gather at gestures of mimesis and mnemonics: the smell of wood, burning wood, the landscape folding into memory, my muscles strained to their limits, the act of writing, the birds, the weeds and their bursts of effluvia, the scent of sweat + citronelle + resin, the texture of the bread, the complexity of my joy with the simplicity of the cashier’s smile – of greengreengreen in every direction but up. This leads me back to my desk, the writing, the fat notebook; I manage to finish the first draft of my novel, which will eventually become BEER MYSTIC. I now invariably also associate this album with this accomplishment, but also the hikes around the barrage and reservoir, the meadow sloping away from the house, the smell of the wine cork, moisture jiggling on blades of grass, creme fraiche with framboises from the garden, playing rounds of reussite [solitaire] while listening to France Culture 93.2 FM discussions about the effects of extreme surprise on the body or the effects of loud rock music on the performances of professional athletes, as I watch the lizard’s detached tail wiggle on the wood floor for half a minute as the color of the sunset blazes, prisms through the wine bottle, a toast to its glory with an evening pastis, fire flies the size of planets, the bats darting through a dusk brimming with the calls of cicadas and toads, swifts and swooping swallows. Do I care to interview the members of Zoviet France? I’ve thought about it; probably wouldn’t mind. I am interested in what they have to say, but for the purposes of maintaining the sanctity and integrity of the music loose from any framing of it in terms of strategy, reviews, or the artist’s aesthetic intentions, it is probably better to know less specifics than more. Never mind the peril of reading an interview with a musician you respect only to discover too much about him or her, leaving you disappointed and the music forever tainted. To be honest, I am more interested in dissecting how the elements of chance fell into place so that my destination plus the music I brought along, plus my ambitions and situation helped to create this magical moment in time with serendipity as the guest conductor. Despite being one of the most compelling entities to emerge from England’s fecund 80s post-industrial scene, Zoviet France remain a largely unheard “band.” And it is in uncertainty that myth and legend are fostered. I prefer mythical to overrated or overplayed or over-cited – enough of crediting the Velvet Underground with starting EVERY trend and fashion since 1966. Zoviet France’s work may be hard to track down, impossible to find in stores, but you can listen to much of their back catalogue on Youtube – so, no excuses. The reason they are there even if you do not notice is that Zoviet France evades the classic capitalist symptoms and marketing strategies of popular music by forcing issues about what music is or should be and they pay the price – or reap the benefits. This elusive round-robin, idiosyncratic collective of sound-shifters, post-ethnic-industrialists, dronologists, and pata-ethnomusicologists, based in the Newcastle area in northeast England is known as :Zoviet*France: but also Zoviet France, :$OVIET:FRANCE:, Soviet France, and :Zoviet-France and has included, among others, co-founder Ben Ponton, Mark Warren [Penumbra] and periodic collaborators such as Neil Ramshaw, Peter Jensen, Robin Storey [Rapoon], Lisa Hale, and Mark Spybey [Dead Voices on Air]. They’ve recorded countless hours of improvisations, splicings, edits, cut’n’pastes, manipulations and many of this on analogue equipment [pre-sound-software], which is key to their unique organic sound, which reeks of wood and dirt. I may even convince you that you are witnessing the evening rites of a tribe lost in our cultural ADHD-induced amnesia. Anyway, it is always eerily, beautifully “other,” hauntingly enchanting like the soundtrack to an unreleased moral mystery-thriller directed by Eric Rohmer or a meditation on nature by Werner Herzog. After dinner, the sun doesn’t seem to want to set as I watched my friends the green lizards scurry after flies. The bats and swallows are also my friends. The surrounding sound, a sharp, tinny buzz in the dusky woods is not a chain saw but the sound of a million insects rubbing their wings in unison. By the end of the summer, my work gloves have formed to the fit of my clenched hands and the sweat, sawdust and resin have left them stiff; they stand upright on the kitchen table like plaster casts and that is how I leave them – as if to say “hello” or “give me your hand.” As much as we may try to adjust to a location, become an actor in a place that has seemingly accepted or tolerated you, you will forever just be an interloper here, walking barefoot on moss one day and broken glass on pavement the next, an intruder everywhere. bart plantenga bart plantenga is the author of the novels Beer Mystic & Ocean GroOve, the short story collection Wiggling Wishbone, the novella Spermatagonia: The Isle of Man & the wander memoirs: Paris Scratch and NY Sin Phoney in Face Flat Minor. Sensitive Skin is hosting 6 short movies illustrating stories from these 2 books. His books Yodel-Ay-Ee-Oooo: The Secret History of Yodeling Around the World & Yodel in HiFi plus the CD Rough Guide to Yodel have created the misunderstanding that he is one of the world’s foremost yodel experts. He recently finished the Amsterdam-Brooklyn novel Radio Activity Kills with his daughter, Paloma. He is also a DJ & has produced Wreck This Mess, in NYC, Paris & now Amsterdam since 1986. He lives in Amsterdam. Frozen Time at London’s National Gallery Taking shelter with a warm cup of tea at the National Cafe on a rainy London day is never a bad idea—coupled with getting lost among the plethora of luring graphics at the National Gallery. While some works seem to summon more viewers than others, there’s a particular painting I keep finding myself at an interface with, while still trying to fathom its meaning. That is none other than the gallery’s most curious, enigmatic, and perhaps even disturbing painting in room 8—or maybe even in the entire National Gallery itself. Constantly drawn towards the same canvas, I read it as a piece of visual poetry where every figure stands for something, and the observer is at the mercy of Venus’s eyes, which continue to tease the contemplator conspicuously about the painting’s hidden meanings. Agnolo Bronzino’s ‘Allegory with Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time’ lacks the typical Renaissance painting’s harmony, structure, and focus--leaving the observer with many things to view, with eyes and minds in a state of perpetual inconclusive wandering. As Venus and Cupid lay there, blatantly enamoured in an almost-kiss--lifelike, not a brushstroke in sight--one cannot help but wonder: ‘what does time have to do with this?’, ‘who’s who?’, or simply, ‘What’s going on here?’ According to Einstein, ‘For us who believe physicists, the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.’ This idea comes into play in Bronzino’s allegory, where all sense of time is glaciated around and within the figures of Venus and Cupid, and Time is embodied in an allegory incarcerated within the physical boundaries of the painting’s ontic reality. Beyond all this, it is interesting, and maybe even a bit amusing to contemplate this Renaissance masterpiece in terms of some modern philosophical theories on time here and there. While savouring the different hues of colour, we tend to find these theories in a medium where space and time are not absolute, but rather, are represented in a two-dimensional continuum. But the painting’s enigma remains unsolvable…there still is a lack of consensus, a large amount of dissention, and varying degrees of certainty on the identification of the painting’s figures. A spooky, hollow, eyeless, and perhaps brainless figure who’s believed to be Oblivion looms above the couple in the upper left corner of the painting, while below her stoops an anguished figure interpreted as Jealousy (and later on, seen by some scholars as Syphilis). Towards the lower right is a twisted, anatomically distorted ‘lady’ holding honeycomb (pleasure) in one hand and her stinging tail in the other--her twisted posture and serpent tail trick the reader into seeing that her right hand is her left, making her known as the embodiment of Deception. By her side, Folly carries roses toward the couple, while stepping on some thorns himself. However, the major focal figure besides Venus and Cupid is Chronus, or Father Time, the white-bearded figure at the upper right of the painting, with his hour glass on the back of his shoulders and his arms about to move a silk blue drape either away from or over Venus and Cupid. One thing that is for sure in the painting is that Time is present, but he is not perceived or experienced by neither of the two ‘lovers’. Many art historians and other interpreters have seen Time’s gesture with the cloth as an attempt at unveiling the couple, but it can also be seen from an opposite vantage point: an attempt to conceal, rather than reveal. I see Chronus’s gesture in that light, by taking into consideration a modern theory on time--namely that of Sartre. Moving forward a few centuries and having Sartre in mind, the allegory suddenly appears to make a different type of sense to me--albeit one that may be a bit far from the painter’s intentions--as some pieces of this intellectual puzzle begin to fall into place. Both Venus and Cupid appear to be completely unaware of Chronus and the other figures surrounding them (Folly, Deception, Oblivion, and Jealousy/Syphilis) in a complete detachment from both time and their experience of it (temporality), which reminds me of Sartre’s notion on time and the dissociation between chronos (clock time) and kairos (the experiencing of time). According to Sartre, ‘time is, above all, that which separates and the only solution for certain individuals is to freeze time, to stop the clock in order to foreclose the possibility of separation. The result is a present that is completely subsumed by the past and where the possibilities of the future are forever denied.’ Since temporality is a vital factor for the occurrence of separation, the denial of chronological time makes way for fantasies of interminability—on Bronzino’s canvas. The painting is typically mannerist in figura serpentina form, and the figures’ appearances as frozen objects in motion actually helps in portraying this rupture in experiencing time; the relationship between chronos and Kairos is destructed, hence leading to the pausing of time, along with the timeless concepts. Looking again, the concept of ‘freezing’—with the act of Chronus’s concealment of the embracing couple—pervades the painting in many ways. There is an icy coolness in the lascivious eyes and pose of Venus and Cupid, who have not usually been seen embracing in that manner. What also strikes me is that despite the passionate embrace, Bronzino seemed keen on keeping Venus and Cupid in the pale, stony color of cold marble, save for the ears and cheeks, which appear to be the only ‘warm’ spots in pink. Besides Venus’s frozen gaze and her complete dissociation from time and inexperience of temporality, the almost-dropped blue cloth reflects a protective measure--the freezing of time is meant to protect Venus and Cupid from the negative costs of pleasure and a kind of denial of the low qualities of love: Deception and Folly are at the right, along with Oblivion and a gruesome embodiment of Jealousy/Syphilis to the left. Folly’s stepping on the thorns may also signify the dangers of accompanying pain of such ‘love.’ The denial of time through freezing it is not only out of fear of separation, but it is out of Cupid and Venus’s fear of the other viles resulting from their transgressive love. Considering the fact that the painting was a gift from Cosimo de Medici to King Francis the 1st, and knowing the latter king’s love for puzzles and symbols, the motive behind Bronzino’s mystification is quite understandable…and perhaps the role of Time will remain unclear in Bronzino’s allegory. But whether the painting really illustrates this peculiar forbidden love’s denial/freezing of Time or not, there is an obvious break in—or lack of—their perception of it. And so, over a warm cup of tea, we continue the post-museum conversation about the loads of work art history still has ahead …until my brain can only respond by constructing a poem: From a spout among the ebony waves, I shake off a pair of tiny wings. A flutter fans its way out, Glossing away from the raven-dark depths, floating off, away from the confused mass, toward the glowing embers of a mysterious flicker …Like a moth to a flame I do not understand. Roula-Maria Dib Roula-Maria Dib is a university professor at the American University in Dubai where she teaches courses of English language and literature. She has published some poems, essays, and articles in magazines and journals such as Renaissance Hub, The Journal of Wyndham Lewis Studies, Agenda, Two Thirds North, and The Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism (ARAS). She is also currently finishing her PhD in Modernist Literature and Psychoanalysis from the University of Leeds in the UK. Her dissertation focuses on Modernist literature (namely the works of James Joyce, Hilda Doolittle, and W.B. Yeats) in light Carl Jung’s psychological theory of individuation, or spiritual transformation. The themes that pervade her work usually revolve around different aspects of human nature, art ekphrasis, surrealism, and the collective unconscious. Luck

The red lane to the lyrical boat tied at an angle to the wharf, a geometrical boat full of rooms tucked between grooves. When he looks into the V’s, vistas open at eye level: pastures accustomed to grass’s green trim and ruminant animal sound. It’s only a façade but he understands it’s to help him pause his conqueror’s stride and become instead a visitor from another country. And the rooms themselves – he fumbles with the key, it lets him into a rose-walled room that leans slightly to the left toward the replica of a gold sun, even though the white mountains through the window make him shiver and notice the cool blue floor that mounds up under his feet. Suddenly he wishes that nobody had sent him here, he wishes this were simply a spontaneous villa his peripatetic wanderings led him to, like a lucky nickel, found in childhood, on someone else’s driveway. Grace Marie Grafton Grace Marie Grafton’s most recent book, Jester, was published by Hip Pocket Press. She is the author of six collections of poetry. Her poems won first prize in the Soul Making contest (PEN women, San Francisco), in the annual Bellingham Review contest, Honorable Mention from Anderbo and Sycamore Review, and have twice been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Poems recently appear in Basalt, Sin Fronteras, The Cortland Review, Canary, CA Quarterly, Askew, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Ambush Review. Triptych

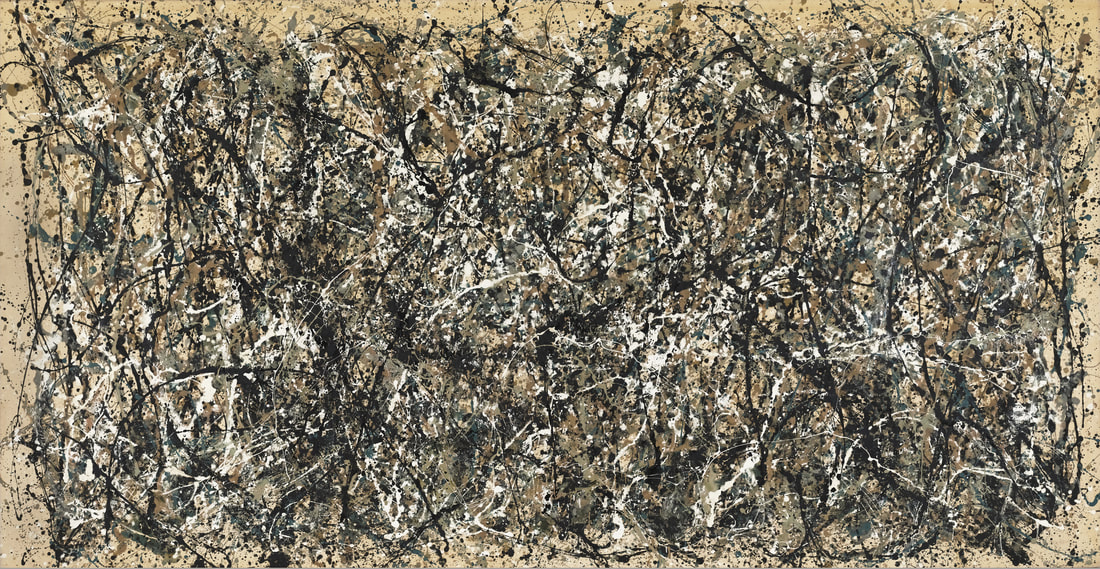

From the beginning you can glimpse the next. Do you remember, from the viewing platform, that climate called “all over,” a diaphanous layering and movement with no centre, no privileged area? In the darkness there, one person’s nightmare and the ocean’s tides are meshed, as is the bursting of a bubble and the clamor for a victim from the crowd, as it is in life. ‘Its colour parallels the picture plane, but does not of itself say which is forwards, what is backwards here.’But then I thought we saw an opening in whorls, which formed as when between the ceiling cracks a gap appears so when it rains a portion of your room gets wet as water in a river drifting on, the way that thoughts drift on -- only the idea of an idea, the clear symbolic rational gleaned from irrational thought, the seeming appearance of a vision--however, light is falling like fall leaves into a well and hence we can not see too well. One can’t always tell, at first, but if you take, reformat this onto a smaller page, then would the line-breaks change, and if so is this therefore what’s called prose-poem—or would it then be only prose, a draft of criticism, section of a unit not yet optimized for oily apparatus? The night condensed the dew upon the windows; the wind-blown twig-grown branches made a fading grid of scrapes, through which we only view the fog outside, where void and solid, human action and inertia are metamorphosed and refined to energy sustaining them, which is their commonest denominator. I remember what I wanted from you, I’ve given up, but still I wait, and at times the solitary spleen of grace escapes the right hand of fantasy, and the tissue of reality. Today it arced across the room, almost to the door, and mixed with the trace of paint spilled on the floor. Here forms and textures germinate and climax, coalesce, decline, dissolve across the surface with no space we recognize or sequence of known time except that seeming never ending present. Although we are not left spinning; a visualization of remorseless consolation is presented—in the end is the beginning. Eric Fretz Eric Fretz studied art history in Hampshire College and CUNY, was a National Health Service union rep in London, and now divides his time between Brooklyn and Beacon New York. He has written sporadically about both radical politics and contemporary art, and is the author of Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography (2010, Greenwood Press). Faces

In this city it is the measure of a lady's face that matters. Not the lift of her shoulders or the length of her legs. Only the distance between cheek and jaw and the spacing of the eyes determines a lady's success. There are no river taxis in this city and we must assort ourselves on the damp benches, pull fragile looking-glasses from handbags, and take measure of our gaze while casting envious glances at the circling river birds always overhead. At night many of the women use a husband's ties to bind their faces painfully tight. So much pain . . . . I must keep my thoughts quiet for it is impossible to live on the wrong side here. Surely more attention should be paid to a woman's breasts, or a well turned ankle, or sleek thigh. Many are aware of this truth I feel sure, but today all the society columns and even whispered gossip must never mention any feature but the face. I keep my plans of escape well-hidden and only take them out at night to write detailed instructions to my future self. Meanwhile I carry a camera in the large pocket of my sweater and take surreptitious photos of the pain in the eyes of the ladies. When I am free and living in another city I will show these photos to my own daughter and she will hurry to the window and cast her love out over the beautiful city with no rivers only wide streets with pristine sidewalks full of contented faces smiling like wildflowers on a hillside, a city in which countenances are free to take their own shape and people who should hang shall be hung. John Riley John Riley lives in North Carolina, where he works in educational publishing. His fiction and poetry have appeared in several print and electronic journals, including SmokeLong Quarterly, Connotation Press, Willows Wept Review, Loch Raven Review, Dead Mule, and Blue Five Notebook. He can be reached at riley27406@gmail.com. The Shadow of Choice

A pause. A sigh. A choice. Always a choice. A body blur stands in the foreground, an inchoate shadow. Shapeless, sexless, ageless. And yet, knowing nothing about this formless being, I feel an instant kindredness. The tendrils of universal hesitation wrap around my heart as I sympathize. "Consider this," the artist seems to say. "Consider the broad and easy way, all pink and glowing in the late afternoon sun." For ahead is an open hallway in a rosy wall, no door impediment to ponder. Just a way that waits, a harmless mouth of opportunity. And at the end of this short shadowed hall? The bright blue of Future. The way of Meant to Be. The painting is deceptively simple. All straight lines—vertical, horizontal, diagonal—except for the sacklike lump of shadow. Is it the deception of simplicity that makes our formless friend pause? On the left, in the deeper shadow of choice, lie three more openings; access to the black halls of unknowing. Two white sentries stand guard. Are they doors open in welcome? Will they swing shut and preclude exit once entered? Are they shields? Blockades? Do they beckon or bar the way? Does that depend upon some unrevealed aspect of the shadow body? Shadow casts itself across all choices. There is no way outside the power of its hand, unless no choice is made. To remain in sunlight is to remain frozen in place. The dilemma creeps through my chest, crawls into crannies of what-ifs and who's to say, questions the nature of my nature, the nature of way, the nature of choice. I become the shadow body, caught in eternal indecision. It's not so simple, after all. Renee Soasey Renee Soasey is working toward completion of a BFA in Creative Nonfiction and toward completion of an off-the-grid home in the high desert of Central Oregon. A Window

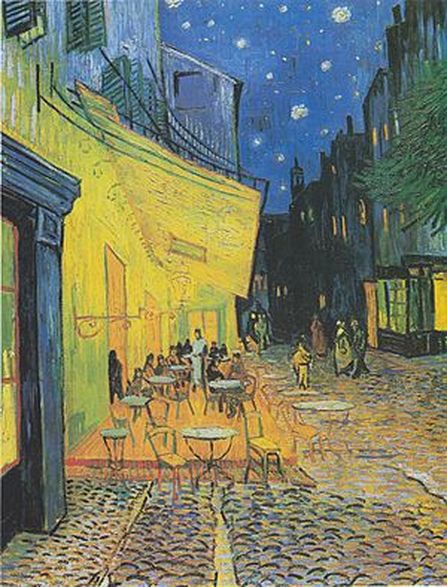

The painting hangs on a light grey, dappled wall in a room where it is the only picture. It rests in a thick, walnut brown, particle board, mid-century walnut frame. The wooden frame has staggered steppes going into its centre, towards the picture, like a Mayan terrace garden. You can see the black lines of the imitation wood grain running the length of each portion of the frame; intermittently interrupted by a scuff or scratch that discreetly reveals the pressboard beneath. It is not ornate. It is most definitely wrong for the print inside of it, but Heather and I found it in this frame at a Goodwill in California and think that it must be in ensconced there for a reason. Plus we feel it would be pretentious to buy a frame for the one print of a painting that hangs off-centre on a side wall in our small, sparsely furnished bedroom. Next to the wall is a bed with no frame. Mattress and box springs rest on a bare hardwood floor. Clothes, books, and paper litter my side of the room on the floor next to the bed. Heather’s side is clean, neat, spotless, immaculate. My side looks like I think no one will ever see my mess. Heather’s side looks like she is ready to entertain company. When I rise in the mornings and see the picture, I ache. I sometimes catch Heather looking pained too. The print itself is beautiful. Oranges, yellows, and reds, and seemingly every hue of blue. The print is of Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night. In the centre of the painting is the outside of a French café. People sit at the tables on the bright orange and yellow deck. Others stroll the darkened street under bright swirling stars nestled in dark blue sky. All of this is performed in the harsh brush strokes and dabs of the world’s most famous and prolific Impressionist. It is a painting of the place Heather wants to live. The place Heather hopes to live. A place we’ll probably never live. The stark contrast of the painting to the disparity of the frame encapsulating it speaks to me. It is both a call to live better and a reminder of my failures. I promised her the world. Instead, I gave her a window into the life she’s always wanted. A masterpiece contained in a beat up frame. Paris contained in a small American bedroom. William Nichols William Nichols is 42 years old. He has been married to his wonderful wife Heather for 17 yearsand they have four beautiful children. He is a medically retired Army Veteran with one deployment to Iraq as a Medic in the 82nd Airborne Division with ten years of service in the United States Army. He is currently a student at Portland State University, working towards a Bachelor’s in Fine Arts in Creative Writing. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|