|

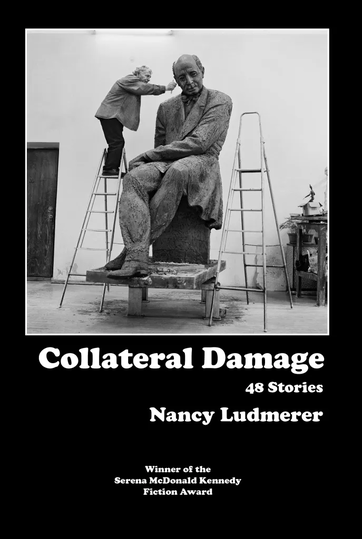

The Ekphrastic Review is pleased to talk with ekphrastic contributor Nancy Ludmerer about her collection, Collateral Damage: 48 Stories, from Snake Nation Press.

Lorette C. Luzajic, The Ekphrastic Review: Your new book, Collateral Damage: 48 Stories, is an eclectic collection of stories of different lengths, themes, and sources of inspiration. Tell us how the title drives the selected works. What does collateral damage mean to you? How does this theme inform the stories, the characters, and you, as the author? Nancy Ludmerer: The title is from a microfiction I wrote and published years before I decided to make it the title of the book. In that 100-word piece, a housefly witnesses domestic violence and then becomes “collateral damage” when the man pounces. As I began to put together a collection, I realized that collateral damage, which I think of as unintended consequences visited on a bystander or other third party, was at the core of many stories. Children are often the collateral damage of their elders’ conflicts, misconduct and mistakes, as in “Hide-and-Seek,” “Adventureland,” and “Heirloom.” Relationships suffer collateral damage via a careless action, word or gesture. In one story, “A Bohemian Memoir,” a wineglass (the narrator) suffers collateral damage while recounting the life of her now elderly and ailing mistress. The book is in two roughly equal sections, Part I: “Collateral Damage” and Part II: “In the Repair Shop.” The stories in the second part also deal with loss but end on a note of hope or redemption. Much of your extensive body of writing work and numerous nominations and awards is for flash fiction. Yet you’ve also written longer stories and nonfiction essays. Tell us what these different forms mean to you. What is it about the short form that inspires you to create? Are there significant differences among them, or are the lines blurred for you? Nancy Ludmerer: I first wrote flash fiction in a workshop taught by the amazing Pamela Painter. The compression, the intensity, and simply studying with Pamela turned me into a fan of the form. I am also someone who revises endlessly before sending stories out (and sometimes even after sending them out). As a single mom working long hours as a lawyer, I found it easier to revise and “perfect” a 300- or 500- or 1000- word story than a 5000-word one. Since retiring from the law in 2018, I’ve had more time to write. My longer stories, including “A Simple Case” (Carve); “Matchbox” (Masters Review) and “The Loneliness Cure” (Orison Books), range from 3500 to 7800 words. Each was a prizewinner, with “The Loneliness Cure” selected for Best Spiritual Literature, Vol. 7, published in December 2022 by Orison Books. “The Loneliness Cure” was my first venture into historical fiction; it’s set in Ukraine in the early 19th century. A new work in that genre, a novella-in-flash set in 17th century Venice, will be published later this year by WTAW Press. “The Loneliness Cure” and the novella are each based on the life of a Jewish woman, extraordinary in and for her time. With the novella-in-flash I’ve been able to use a form I’m very comfortable in to craft a longer work. My essays address specific subjects that didn’t lend themselves to fiction or short forms. “Kritios Boy” (a Literal Latte prizewinner, which was cited in Best American Essays 2014) is a memoir of teenage love and its aftermath; “Mr. Right” (Brain, Child) is about my 94-year-old widowed mother’s stated intention to remarry; and “My Jonah” (Green Mountains Review) is about the name I gave my son, including my exploration of the name’s significance in Jewish, Islamic, and Christian traditions. Using these essays as an anchor, I’ve put together a chapbook (still seeking a publisher) called Some Things Happen Twice made up of these three essays and half-a-dozen flash fictions, along with one somewhat longer piece of metafiction. The people in the essays (mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, and lovers) reappear with different names and in somewhat different – i.e., fictionalized -- situations in the flash fictions; hence, the title for the collection (and one of the flash stories). The final story, “The Year of Four” (Chicago Literati) is a metafiction that plays with form and, in its own way, sheds light on everything that has preceded it – memory, motherhood, naming, and the craft of writing fiction based on life. Your stories are inspired by very specific situations or motifs, but from such a range- horror movies, Jewish culture, musical performances, an autographed baseball, famous paintings, a self-help technique. Tell us a little bit about your process. How do you grow a story out of these details? Nancy Ludmerer: A story may begin with a name, a prompt, a moment or an incident – sometimes from my own life, sometimes something I’ve read or heard about. For example, as a child, I heard the song “Scarlet Ribbons” and it stayed with me for years until a prompt from Amanda Saint in a flash workshop turned it into a story. That prompt was to write a story in the first-person plural with the opening clause “We wanted to be ____”. The story that resulted, published in Mid-American Review and reprinted in Collateral Damage: 48 Stories, is “Fathers.” A number of the details you mention – the film “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” (which makes an appearance in “Fathers”) the autographed baseball (the key object in “Heirloom”), and the Mozart aria “La Ci Darem La Mano,” which is translated as “There I Will Take Your Hand” (the final story in Collateral Damage: 48 Stories) -- connected with stories I was working on. The details were transforming; stories that felt flat took on new life. You had another life as a lawyer in New York City. What part of this work do you bring to your work as a writer? Nancy Ludmerer: In litigation, your first job is to learn everything you can about the facts and the law. After that, you distill a case to its essence, so you can present it to a judge or jury. Flash fiction, of course, requires compression: telling a multi-layered story in a page or two, knowing what to leave out, and crafting the ending that’s right for the story. It differs from litigation in that the ending you seek in any short fiction should, at its best, be both inevitable and surprising – not the effect you necessarily want in your advocacy! Research, revision, deadlines, page and word limits – all these demands on a litigator apply to writing short fiction as well. I’ve occasionally drawn on my legal experience for subject matter, particularly my pro bono work representing or counseling prisoners, victims of sex trafficking or domestic violence, illegal immigrants and disabled individuals. Two stories in Collateral Damage:48 Stories, “Family Day” and “No Offense” concern the heartbreaking situation of an incarcerated woman whose child is placed in foster care. Another flash (this one not in the book,) “Learning the Trade in Tenancingo” is based on research I did in connection with counseling women who were potential victims of sex trafficking. Of my longer stories, several have legal underpinnings. “Matchbox,” is based in part on my visits with prisoners at a maximum-security women’s prison. “A Simple Case” is loosely based on a personal injury case. I have under submission a collection entitled “In the Shadow of the Law” which includes these and other stories. Some of your stories, including a few in Collateral Damage, and some others that we have published are ekphrastic. One of them was a finalist in our Ekphrastic Cats contest, and another was nominated by TER for a Best Microfiction award. Tell us about your relationship with visual art. When your stories bloom from a visual art prompt, what is your process like? How do you engage with the artwork? How do you choose the art, or does it choose you? Nancy Ludmerer: “The Decision,” the microfiction that was a finalist in the Ekphrastic Cats contest, had its origins in the pain of having to put down a beloved cat. When I first conceived of the story, my heart was too broken to send the story out into the world. The Ekphrastic Cats competition, with its wonderful array of artistic felines, some alone in their grandeur, others with their “significant others,” enabled me to complete and submit that story. The micro “At the Pool Party for My Niece’s Graduation from Middle-School” began life as an eight-page story many years ago based on an overheard snippet of conversation. The story languished in a drawer for nearly two decades. It wasn’t until I viewed David Hockney’s brilliant painting Pool with Two Figures and cut the story to its essence that it worked. I was so grateful to TER for publishing and nominating it. Two of my longer stories were prompted by paintings. “Head of a Dog” (The Hong Kong Review) was based directly on the Edvard Munch painting of that name. As the canine narrator tells us, “The Munch painting, with its muddy greens and oranges for the dog’s fur, the dog’s black eyes like olive pits, made me afraid to look in the mirror. . . [E]veryone reveres Munch’s painting, The Scream. But no one knows Head of a Dog, which is equally striking, where the dog – unlike the Screamer – remains stoic but courageous in the face of disaster.” Another story, “Fall on Your Knees,” published originally in Fiction Southeast and reprinted in TER, was prompted by a Gauguin painting. It’s a story about art and sexual exploitation. Both stories involve the law in some way, too – a police investigation in “Head of a Dog” and a prosecution in “Fall on Your Knees.” Neither story would exist if not for the artists’ gripping work.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|