|

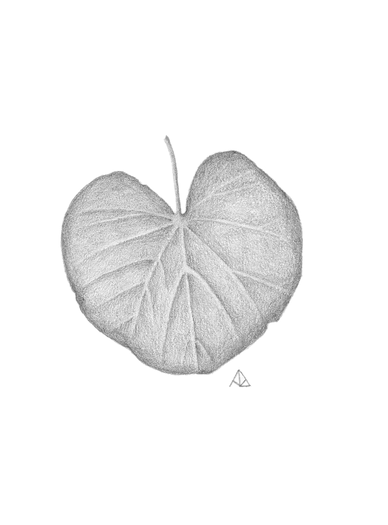

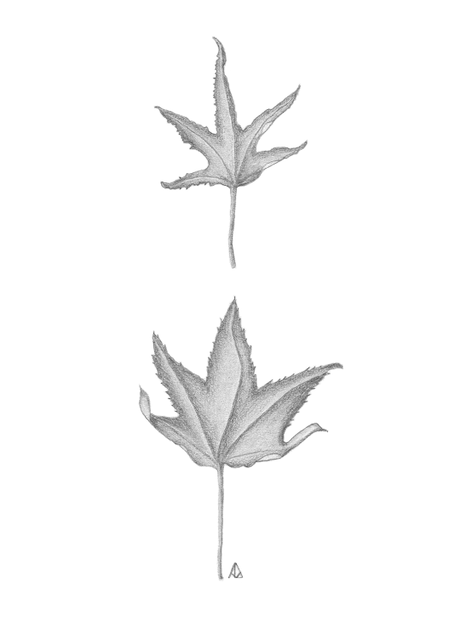

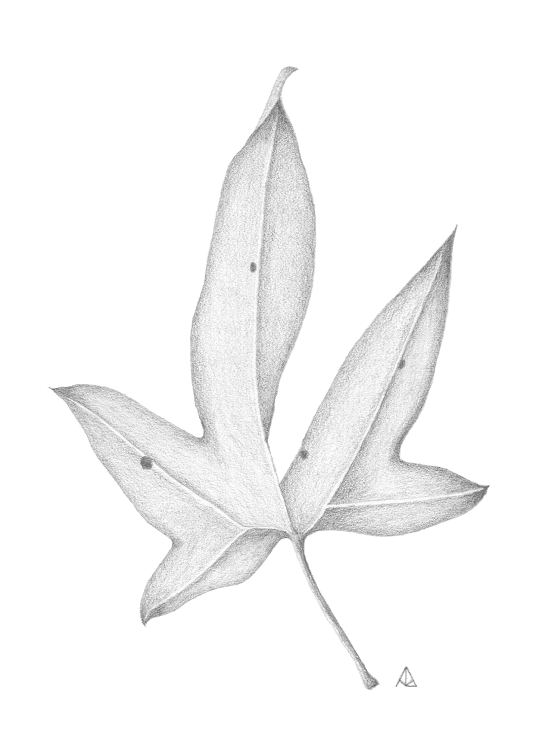

Book Review by Kate Flannery Kitkitdizzi by Ann Brantingham and John Brantingham Bamboo Dart Press 77 pages Click on image above to view or purchase from publisher. Communion and Transformation in the High Sierra When I was growing up in the Pacific Northwest, my summers were spent either on the North Oregon Coast or camping and hiking at the base of Mt. St. Helens. Both places made me feel very small, and, of course, I was by comparison to the ocean and the mountain. Being small in the midst of big places can give you a tantalizing invitation to be transformed, to begin to know and become part of a place by exploring the other small things around you: wading through grasses at the beach, wondering about sea creatures who lived in the sand dollars you pick up, tasting the sweetness of salmon berries before the bears get to them, and skidding down pumice trails in a fir forest. These are things you can know. These are things you can take in and hold close. It is these small and quiet essences of a place that invite you gently into communion with things greater than yourself. And it is this communion that Ann and John Brantingham offer us in Kitkitdizzi, a new volume about the Sierra Nevada from Bamboo Dart Press. Words can’t capture the Sierra. And, to my mind, visual representations also lack something in calling forth the experience of this vast area. Words and pictures, separately, can come close, but when someone gives you textured words accompanied by the most articulate of drawings, you can take a transformative leap toward the Sierra’s mystery and timelessness. Most writers and artists have focused on the grandeur of the Sierra: the granite and the ice, the rush of rivers and the giant trees. But Kitkitdizzi takes us down a different path, one filled with quiet and peace. And this, for many of us who love the Sierra, is the heart of it all. The Sierra Nevada are a grand array of mountains, meadows, rivers, and canyons. Its animal inhabitants are as varied as the terrain. Writers and artists have tackled and tried to capture it for hundreds of years, from John Muir to Kim Stanley Robinson, from Leland Curtis to Ansel Adams. To approach the Sierra is humbling; their draw is inescapable. Kitkitdizzi pairs the words and meditations of John Brantingham with the delicate and nuanced details of Ann Brantingham’s drawings. And it is a match beautifully made. Together these two continually reveal the quiet persistence of the Sierra. As John weaves his way down paths he has known since childhood, we get to listen to his wonderings about who he is and where he belongs. He explores his own inner landscape and invites us to explore our own. Ann’s art perfectly complements and reflects these musings as she draws us in to the complexities of the plants and growing things, compelling us to see the abiding presence of the place in its smallest, most intimate moments. The title of the book refers to one of these small things in the Sierra: a low bush or groundcover that grows best in the sun and along pathways in the high country. Because of the distinctive odor of its leaves, it is not appreciated by everyone, but there are those, like John Brantingham, who love its scent; he breathes in deeply as he walks by and brushes its branches. The silence of the Sierra is a bit like that, Brantingham explains. Not everyone likes the quiet of the backwoods, he says, but it is clear that he and Ann have found the place to be transformative. Ann’s drawing of the Kitkitdizzi plant, appearing on the cover of the book, misses nothing of its habit. She shows us every detail of the small, frondlike leaves, composed of leaflets which are in turn regular gatherings of even smaller, frilled leaflets. You almost believe you could touch the image and come away with some of Kitkitdizzi’s sticky resin on your fingertips. The range of John Brantingham’s wonderings is immense, whether he’s telling us about sitting around an evening’s campfire in the midst of bats dancing, or running with a bear down a mountain slope terrified by an approaching storm’s lightning and thunder. He can speak eloquently of his solitariness, “lost in the long thoughts,” as he takes notice of a Sooty Grouse nearby. And he can speak just as eloquently, in first person plural, in the voice of a community of artists and poets walking to Heather Lake, each of them letting their memories unfold. The range of Ann’s renderings of the leaves, flowers, and other creatures of the Sierra is also impressive. She gives us a scarred and anonymous “Leaf from Wuksachi” as well as a trio of manzanita leaves, immediately familiar to anyone who has trekked in the Sierra. Rather than show us the large, white sepal blooms of the dogwood trees which often nestle under the giant sequoias, she meticulously draws the underside of the dogwood leaf, a part of the tree which is overlooked more often than not. Rounding out the array of her artwork are the drawings of the Rubber Boa and the Ceanothus Moth, both small but essential parts of the life of the Sierra. These renderings from the Brantinghams focus not on the grand things of the Sierra, but on the intimacies of mountains and meadows, rock and stream, insects, birds and bears. We see the tenacity of life that exists there even when devastated by fire and invaded by humankind. Kitkitdizzi offers us the small exchanges that can occur between human and place, and by them we are transformed and moved to a new plane of understanding, a new world of quiet, a new sense of wholeness. Kate Flannery Read Kate Flannery's "14 Stations- an Experience of Despair" and Faith in The Ekphrastic Review Kate Flannery is an Editor-at-Large for The Journal of Radical Wonder where she writes the column, “Interludes.” Her essays, poetry and fiction have been published in Chiron Review, Shark Reef, and Pure Slush, as well as other literary journals. She was a finalist in Bellingham Review’s 2022 Annie Dillard Award for Creative Nonfiction. Running with the Bear In the morning, I hike up to Heather Lake alone, taking nothing but the clothes I’m wearing. It’s sunny and warm so I wear a tee shirt, shorts and running shoes. It’s a long uphill climb, but the day cools by degrees, and by the time I hike the four miles, it’s clouded over too. The view is beautiful. On one side Alta Peak rises out of the treeline and is snowcapped. On the other, I look down past Tokopah Falls to the canyon where the Marble Fork of the Kaweah River rushes toward Lodgepole. I walk back to camp in a different direction than I came, cresting a mountain. Just as I am on the broad and flat ridgeline, the clouds darken up, and it starts to rain. I speed up my trudge, which is made easier by the fact that I’m going downhill. Soon, the rain gets harder, and in ten minutes it’s hailing, the little stones stinging my skin, but they don’t really hurt, and the day is so cool, I start to jog downhill. In a moment, the lightning starts, but it’s not directly on top of me. I’ve never had a moment like this before, running through a lightning and hail storm, the thunder like something out of a Wagnerian opera. I’m going down the ridgeline which is perhaps only twenty yards wide, so when a black bear sees me charging, he assumes there is something to run from and starts his own gallup downhill, running in a kind of easy lope. For a moment, maybe five seconds, we’re running together, me on the trail, him through the trees, but together. I will try to explain the sensation of running with a bear through the lightning and hail when I get back, but it falls flat with everyone I tell. John Brantingham How to Be Alone One of the first things I have to do when we come up to the mountain is to relearn how to be alone. For Annie, it’s less difficult, I think. She’s comfortably alone, and she works out of the house. She’s by herself most of the time and knows how to be there. Besides, she’s an introvert. I am, however, an extrovert, and during the semester, I am surrounded by students and colleagues. I like to be with people and to hear them and to talk with them about everything. They give me energy. As the semester builds and my stress level grows, people give me insulation from the self-doubt that I live with. I am a born worrier and over-thinker. I feel guilt for things I have done even when they were the right thing to do. By the end of the semester, I find myself seeking people so I don’t have to think about those things that are bothering me. They are distractions, and I need them. I, like so many people, have a number of addictions. The most powerful of these is the distraction I get from being around other people. I feed this. When I am not with students, I seek out my colleagues. I am on Facebook constantly, and I get a little high every time someone likes my post or comments on it. I have three email addresses for three different groups of people. It’s not healthy to always be alone, but it is equally unhealthy to search for a group of people to help dispel the alienation and boost my endorphins. I am not alone in this. The world, as Wordsworth put it, is too much with us. He wrote this line in 1802, and it hasn’t gotten better, and my mind magnifies and creates problems, so soon I am thinking about all of the ways the world has failed me, or I have failed it. The first part in learning to be alone is trying to go cold turkey. Connection to people is my drug. Silence is sobriety. We generally leave during the night to avoid traffic. Annie usually sleeps, and I try to turn off the radio. My drug is talking to people, and I do it to distract myself from painful thoughts, so I sit in silence for as long as I can take it as my mind goes over every slight and every failure, real and imagined, in my life. I sink lower and lower into an evil depression until I can’t take it any longer. Usually, this lasts about two hours. That’s when I turn on the radio or put on an audiobook to distract myself. It’s like this for days as I am setting up camp and getting ready for the next weeks or months in the mountains. Annie is there, and she’s happy to talk to me. It’s good to talk to her, but I can’t yammer on constantly. Anyway, I’m trying to cure myself. The key is not to distract myself. The key is not to be frightened of those thoughts. After a while they’re not crowding in on me all at once. It’s not a hurricane in my mind where I flit from one negative thought to the next. When that happens, I let my misgivings come, and I think my way through each one. Once I have thought about it and decided whether I can do anything about it, I can let it go. This is the hardest part of the summer and the most difficult part of learning to be comfortably alone. If you are like me, and the world is too much with you, and you rely on social media and conversations to get through your day, this will be the hardest part for you as well. I find that it lasts a torturous three days. By the time that is done, I can do the real work of finding my own place in this world. Learning how to be alone is both the most difficult and most important thing that we are doing. It forces a retraining of my brain. At the beginning of the semester, what I am doing is trying to help my students and my colleagues as much as possible. By the end of the semester, I am addicted to the stress. I both hate it and need it, and I am often looking for problems where they don’t exist simply because that is what I have been doing, and it is the only thing that I have been doing, for the past months. Eventually, I cannot see the world except through the lens of my frustrations. It is not necessary to go into the forest to find what I am truly looking for. I could do this at the ocean, in the desert, or even in the city. It’s easier for me to find that thing in the forest because away from the Internet and my responsibilities I can see my addiction to stress for what it is. It’s also easier to see what is truly meaningful and what simply does not matter. I go into the forest, therefore, not to find what is outside in the world, but to discover what is inside of me. John Brantingham Ghost Owl I have always loved it here in the High Sierra at night, and it is magic this evening, when the owl drops out of its branch and floats above camp, going after a rodent I suppose, but there’s something so unearthly about the way it moves through the sky that it seems more metaphor than living animal, or so are the thoughts I have when sitting alone in the dark next to a fire that’s almost out watching the stars. I supposed I have seen owls flap their wings, but I can’t remember it. Mostly what I remember are nights like these when they have come out of nowhere and disappeared in a moment. I have never been with anyone when this happens, never been able to poke someone and point and talk about what we both have seen. In this, for me, they are like ghosts. They’re so odd, so beautiful that I don’t know if what I have seen is real, and there is no way for me to confirm that what I just witnessed wasn’t a part of my imagination. Tonight, I look up from my chair in this camp I have returned to for forty years now to see the face of a teenage boy hanging in the darkness, watching me. He’s too skinny and wears a black Member’s Only knock-off jacket. He tilts his head and watches me, silent and trying to figure me out. I say, “John,” and he’s gone. This, I understand, is the ghost of me, fourteen years old. He has slipped out of the cabin after everyone else went to sleep. Tonight, he’s seen his first owl, and he thinks there’s something magic about sneaking out and seeing that, like maybe he’s cheated the world, like maybe this signifies that he’s special somehow, destined to see things and know things that others can’t. I don’t know about all of that, but I know that he’s right on one count. Seeing that owl was magic. I want to speak to him, and I remember where he went after he saw the great bird, so I douse the campfire and move toward the meadow where I spent so many of my childhood nights. There’s a spot where I could sit on a rock and stare out across the grasses and just lose myself in not thinking. I trudge my way through the night, no longer moving silently the way I would back in those days. Now my feet are heavy. They kick up dust behind me. That kid up ahead of me, hiding from me, the ghost of the boy I used to be, doesn’t trust adults, I know. He won’t trust me now. He trusts things that don’t lie to him. He trusts birds and rain. He trusts the earth and the thoughts buried deep in his head. This year will be a year of owls for him. He’ll be walking through the desert in late fall when he must come close to a nest and an owl buzzes him again and again. He will spend a night in a quarter mile square deep in the High Sierra listening to an owl call and trying to find it in the dark. He will be sure he saw one swooping over his Los Angeles neighborhood and not be able to convince anyone that he did. I want to let him know that I believe him. He’s there at the meadow, alert to me and my heavy steps. He watches me from the rock, and I stop as I would stop so as not to spook a wary animal. We stare at each other for a moment, and then I blink, and he is gone. Who knows where he is now? He can move through the woods better than anyone I’ve ever known, and I’ll never catch him. Anyway, I should let him be. He is lost in his dreams of owls, and that’s not a bad place to take up residence. He will haunt these woods forever. John Brantingham Sooty Grouse

Up near Alta Peak, I come upon a male sooty grouse. He is standing on the edge of the cliff looking down into the hundred foot chasm below him calling in a throaty voice. I am not a birder although I have always admired them, so I don’t know what exactly his call means. Perhaps he is calling for his mate who has gone down into the canyon. Do they fly? I don’t know. Maybe he has just lost the love of his life. She has died, and he is calling after her. Maybe he is just trying to locate friends. I am alone here on this mountain, the only person on this trail as far as I know, perhaps the only human for ten miles, and this is my afternoon. I look out with the grouse past the city of Three Rivers to the San Joaquin Valley, and he thinks about his family, and I think about my wife. Finally, there is a call back from down below. He cocks his head, and it comes again. He’s the size and roughly the shape of a small chicken, so I’m surprised when he bounces off the edge and flutters down. I watch him make his awkward way through the air into the valley floor, and realize that I am here to witness a kind of truth, but I’m not sure exactly what it is. I don’t know how to articulate it, and there’s no one to talk it over with, and anyway what would we say? In any case, part of the truth has to do with the fact that I am completely alone here, apart from all other humans and lost in the long thoughts possible only when I am. John Brantingham Read "The Bottles," by John Brantingham in The Ekphrastic Review Ann and John Brantingham met in London on a joint study abroad program through Mt. San Antonio College and Rio Hondo College and fell just about immediately in love. They were drawn together by a joint passion for art, literature, the forest, the city, dogs, and each other. They’ve tried to live their lives compassionately, and they believe that compassion is their highest purpose and most noble aspiration. They came closer to their own humanity in Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks where they volunteered and lived for nine summers in a van. The time they’ve shared with the volunteers, employees, and friends up in the parks means more to them than they can say. What they hope more than anything is that you disappear into your own natural haven and find out a little more about yourself. They keep discovering who they are again and again.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|